PUBLIC ART AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF WATTS PENINSULA

Presentation to U3A, 2019

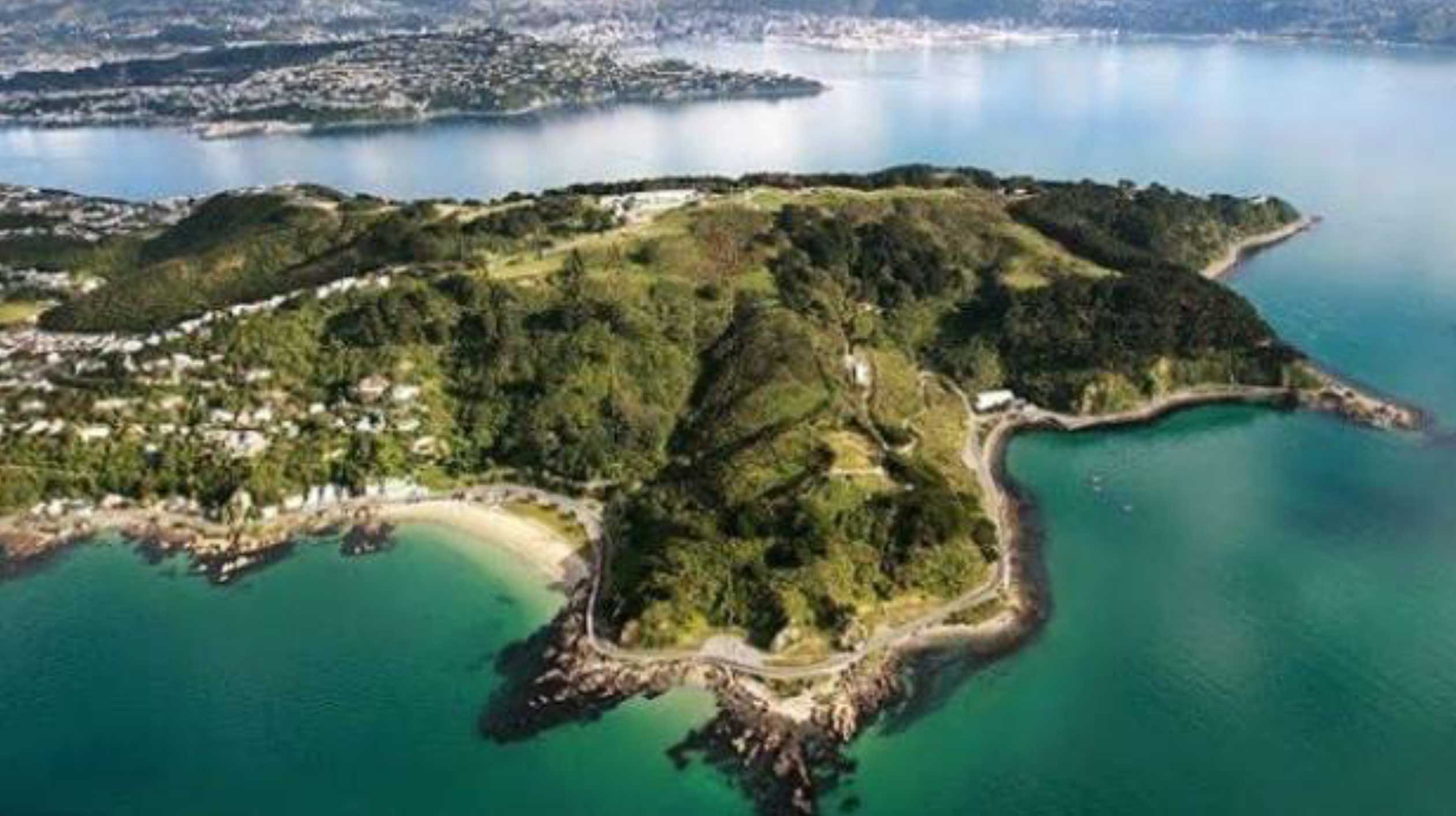

Watts Peninsula, Wellington

An amazing opportunity, never to be repeated, has opened up for Wellington. It is quite remarkable that it obtained no attention in the recent local body elections.

A vast swathe of land known as Watts Peninsula, the peninsula above the Miramar side of Evans Bay, has been declared surplus to central government requirements and passed to the Wellington City Council for development and management. This opens opportunities on a grand scale: there is no other piece of land of this scale, this close to the central city, that will become open for new prospects, fresh ideas, for Wellington City.

The land is likely to have some heritage designation, in turn respecting two aspects of its history: its pre-European uses and its post-settlement military history, such as the Point Haswell Battery.

I want to outline a potential use for part of this land that has the prospect of becoming a stunning attraction, and an economic asset, for Wellingtonians and visitors alike. It is a use that can fit comfortably with any heritage underpinnings the land may have, and that can reinforce Wellington’s aspirations to remain the cultural and art capital of New Zealand.

Watts Peninsula, Wellington

There are two components of this proposal: a sculpture park and a major work of land art. Let me explain.

Sculpture parks are open spaces with outdoor, three-dimensional art works placed around them. And so they feature concentrations of art like an art gallery, but you do not need to go to an art-focussed institution to see them. Unlike a gallery they are not exclusive. The sculptures happily co-exist alongside other features and activities – buildings, if you need them, walkways, cycle paths, picnic spots, play areas for frisbee or whatever, forest areas, ponds and lakes and wetlands, preserved heritage sites…they fit with a wide range of other uses. They are parks with the additional interest of showcasing art works.

Here are three world famous examples:

Henry Moore at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Henry Moore at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Jaume Plensa at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

1. The Yorkshire Sculpture Park, probably the most famous of many in Britain. It has wide open grassed spaces and combines good walking and fresh air with intriguing art, each piece carefully sited so that nature and the manmade offset and enhance each other.

Chakaia Booker at Storm King Sculpture Park

Chakaia Booker at Storm King Sculpture Park

Sculptures at Storm King Sculpture Park

2. Storm King Sculpture Park, in New York State, probably the most famous of many in the United States. It is on a vast scale, almost too much to see in one visit.

Middleheim Sculpture Park (above and right)

Middleheim Sculpture Park (above and right)

3. Middelheim Open Air Sculpture Museum near Antwerp in Belgium, which has probably the best “classical” collection of Twentieth Century sculpture.

Such parks, even when they take hours of travel from major cities to reach them, attract a wide range of people. The Economist was inspired to note their appeal a year or two ago, calling sculpture parks the “hot new British summer destination (with) culture with fresh air.” The isolated one in Yorkshire draws over 500,000 paying visitors a year.

New Zealand is well served with top-flight sculpture parks – but Wellington isn’t. The best are all in Auckland. In fact, the Auckland region hosts two of the world’s great sculpture parks, and what marvellous attractions they are. The Wellington Sculpture Trust and other Wellington art institutions periodically arrange trips to Auckland to see these and they are almost invariably sell-outs. They are:

1. Alan Gibb’s Gibb’s Farm on the Hokianga

Neil Dawson at Gibbs Farm, Auckland

Neil Dawson at Gibbs Farm, Auckland

Leon van den Eijkel at Gibbs Farm, Auckland

2. John and Jo Gow’s Connell’s Bay Sculpture Park on Waiheke Island

Gregor Kregar at Connell’s Bay, Waikeke

Peter Nichols at Connell’s Bay, Waikeke

But they are not normally open to the public and access arrangements need to be made.

There will be a question of what sort of sculptures could be installed in a Watts Peninsula sculpture park? Probably art that reflects New Zealand contemporary practice, which is wildly diverse. The works could be figurative or more interpretive, abstract. They could be permanent or temporary. They could be made of any material within our imagination – steel, sticks, plastic beads, wood, marble or other stone, and so on.

They could be reflective of Maori and other cultures. It is not for me to say how a Maori relationship with the land might be captured in an outdoor art work, but an example already in Wellington is of Brett Graham’s Kaiwhakatere The Navigator, on the former Broadcasting House site behind the Beehive, which in itself creates an inner city sculpture park.

Brett Graham’s Kaiwhakatere The Navigator

And some pieces could reflect the military uses of the past. They don’t have to be like the marines landing on Iwo Jima! Who knows what an artist would produce with the right brief.

Iwo Jima monument

Personally, I think there is scope for whimsical and popular art, works that families and all ages and cultures can enjoy, without necessarily pursing works acclaimed by the world of professional art.

Paul Dibble, New Zealand War Memorial at Hyde Park

Then it may be asked, who pays for it? My estimation is that an initial three or four sculptures would be funded by generous benefactors and organisations like the Wellington Sculpture Trust. Beyond that, there is no need to hurry, there is no problem with the park being a work in progress over a long period of time. In fact there are advantages. Progressive development means that there will always be something new, and the sculpture on offer will not be locked into the approaches of one decade.

In any event the ratepayer should not be solely responsible but be helping out as appropriate with funding already budgeted for in the Council’s public art fund, as is the case with sculptures commissioned by the Wellington Sculpture Trust.

Another funding approach would be based on the model of a third Auckland park, that at Brick Bay Sculpture Trail on the Matakana. There the sculptures are provided by the artists and are available for sale. I do not think the turnover is particularly high, but in terms of visitor appeal the arrangement is highly successful. The relationship of the sculptures to the landscape is particularly good with the sculptures in more enclosed and forested areas, so that you come upon them as a surprise while enjoying the bush, as well as sculpture in ponds and water features. I believe it is a model that has much to offer in thinking about Watts Peninsula.

Utopia by John Reynolds at Brick Bay, Matakana

Fatu Fe’u, Brick Bay

Fatu Fe’u, Brick BayAnd there are further options for creative fundraising. A Sculpture Walk of Art which would attract many smaller donations has been a proven approach overseas, as at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

The sculpture park would need management, both generally in terms of park maintenance, pathways, signage and the like, and more specifically in the choice of sites for sculptures and the selection and installation of these. It is not difficult to conceive of an organisational framework that would deliver on these things, and I would regard it as open ended at this stage as whether it would be an in-house Council structure or a more independent body.

Land Art

The option of land art is related but different. The land itself is moulded into an art form. Artists use bull-dossers, cranes, front-end loaders, the works. This is a type of art that has just taken off since around the 1970s and is rapidly gaining in popularity. The famous scene setter is the Spiral Jetty in a lake in Utah in the USA. There are now some recent and fabulous examples. For some reason Scotland has become an in place for this art form.

Land art at Storm King in New York, by the very famous Maya Lin, the designer

of the Vietnam war memorial on the Mall in Washington DC.

This

is from The Garden of Cosmic Speculation at Dumphries, Scotland.

Another example at the Crawick Multiverse, also in Scotland.

You can sense the appeal and popular attraction of these creations.

As with sculpture parks, so with land art: we have a few good examples in New Zealand, and they are all in Auckland.

At

Gibbs Farm, an example by Maya Lim called

‘A Fold in the Field’.

‘A Fold in the Field’.

At

Brick Bay, an example by Virginia King, ‘Koru’.

I cannot think of a better spot near Wellington that is suitable for a major work of land art, to bring in people of all ages to marvel over and explore and to tread on, to be intrigued by art on a grand scale. Imagine the highest point on Watts Peninsula, a great lookout over Wellington harbour and its surrounds, being accessible by an artwork of a moulded pathway like one of those in Scotland.

Another side to outdoor art is the popularity of art and sculpture short-term events or presentations. The most famous in New Zealand is Sculpture on the Gulf, where for three weeks every second year a fine walkway of temporary sculptures is installed on Waiheke Island. A number of spots around the country have emulated this in variants of one sort or another. Sculpture on the Peninsula, at Governors Bay on Banks Peninsula, has a powerful head of steam. All sorts of competitions, prizes and public participation can be wrapped around these. Events like these would be a natural for a park on Watts.

So that’s the proposition. The Watts Peninsula development plan must make provision to incorporate art. Land art, sculptures and three-dimensional art installations in park or forest land, art and sculpture activities and events. A highlight for Wellingtonians, a new tourist attraction incorporating the heady blend of accessible art with our stunning scenery and outdoors. A locking in of Wellington’s role as the cultural, art and creative centre of New Zealand.