USA/ANZUS, 1967-71

From chapter 5 of the memoir Compass PointsThe year of ‘economics’ was a great mixture too. I was assigned partly to EEC trade matters, and specifically the problem of picking New Zealand apples in orchards in a way that retained their stems, so that they met EEC entry requirements. Without the stem they started to go bad rather quickly, around the depression at the top of the fruit where the stem would be. I didn’t need to know much about the science of all this, my job was to make sure that all the officials in MAF and elsewhere received all the reports from Brussels, and that a properly co-ordinated reply went back. But more demanding was being assigned to be secretary of the Cabinet Economic Committee. My taskmaster there was Ray Perry, secretary to the cabinet, and he pored over my draft minutes with pen poised in more detail than I have ever had before or since. It was a good introduction to both the range of economic and trade issues facing New Zealand, and to the ways of operating of our most senior ministers in the Holyoake cabinet.

In early 1976 the question came, would I go to Washington? I said I would reply in the morning, and talked it through that night with Rachel. But there was not a moment of doubt for either of us — the answer was yes.

We had been back from Samoa for two years, and were fully ready to see more of the world. The time since Apia had flown: we settled into our Wilton house and licked the lawn, yard, garden and inside into shape; we continued to visit my parents’ holiday house at Foxton Beach; and we had another child — Gillian delivered on our hopes for a girl, in October of 1966.

I was mystified that not everyone shared our enthusiasm for accepting the posting. The strand of anti-Americanism in New Zealand thinking became obvious. ‘How can you bear to go there? It’s a racist country.’ ‘How are you going to survive there? It’s one great urban mess from Washington DC to Boston.’ ‘Why are you going? You can’t even breathe the air, it’s so polluted.’ It was mixture of distaste for American capitalism, as perceived, accentuated by New Zealand’s own quite socialist past; of America’s racial history, compared with our own (as perceived!); and of the little guy’s envy Home and abroad, Wellington and Washington of the big guy. None of it deterred us for a moment.

We had plenty to do on the home front before departing. Work on the garden at Rutland Way needed heavy duty, from pouring concrete retaining walls to plantings on the steep slope above the house. We were still doing this on the day of our departure, but we reckoned we were presentable by the time it came to leave for the airport. We were now five, with Gillian only about six months old, but were a good team.

We had a daytime landing in Honolulu with a two-hour stopover. Having never set eyes on the place, we piled into a taxi and drove around pineapple plantations and a couple of villages. The plane was waiting our return and we were dashed out across the tarmac, with high embarrassment as the last passengers to embark.

A two-night stopover in a motel in Los Angeles started us on the learning curve of how different two English-speaking countries, both descendants of Britain, could be. ‘Food to go’ we could work out. The first night menu, at a Mexican restaurant around the corner, was more difficult. Mexican cuisine had not reached any part of New Zealand that we knew of. Taking a stab, I said to the waitress. ‘I’ll have taco, please’ — pronouncing it ‘tack-o.’ ‘Whaaarrrt?’ she replied. I repeated my request and she repeated her version of ‘What?’ I pointed to the menu item. ‘Oh, you mean taaarrrco.’ I humbly agreed.

Three days later in Washington DC another food-pronunciation crisis developed at the hotel’s breakfast room. We went up to the counter where a fast-order cook was under pressure. Rachel ordered bacon and eggs. ‘Uporover?’ was the abrupt reply. Rachel hesitated, having no idea what the question was. ‘Uporover?’ came the impatient demand again. ‘Yes,’ she said, but that did not help! I realised he was asking, up or over, and from reading the popular American weekly Saturday Evening Post which my parents bought from time to time, I had heard of sunny-side up for eggs, and guessed ‘over’ was an alternative to that. I said ‘up’ as quickly as I could and we were able to proceed without egg on our faces.

But meantime we had been to Disneyland. Pirate ships, space rockets, the works. What were the lasting impressions? I was taken by the total commitment to cleanliness, never having seen teams of workers sweeping up every piece of paper or stray leaf as it dropped. And the patriotism. American flags everywhere, and the hallowed silence of an exhibition of Abraham Lincoln and the Gettysburg address. The contrast with New Zealand’s subdued respect for its history and nationalism was acute.

In Washington DC we had to find a house to rent. There was the constraint of a rent ceiling above which the government would not pay, the desirability of living in rough proximity to where some of the other embassy staff lived, and the strongest advice, ‘Washington summers are so hot and muggy, you must have air conditioning.’ It took quite a while but we found a brick place we liked very much, across the border from the District of Columbia in the Maryland suburb of Wood Acres — except that it did not have air conditioning. Well, we thought, we have lived in Samoa without air conditioning, it can’t be worse than that, and so we took it. That was April, springtime.

The city was stunningly beautiful and fresh at that time of the year. All around the Mall were cherry blossoms, and in the suburbs dogwoods — trees with white flowers that we had not seen before — and azaleas were everywhere. We moved in and by June we were struggling. We approached the owner, would he do some deal, like go 50-50 on cost, to air-condition the house? No. We decided to buy a window air conditioner to put in the den, to give us one room we could escape to when the humidity became unbearable. By July we were pricing full air conditioning. It turned out that the cost was manageable because the cold air could use the same ducts as the winter central heating. We were wrung out, maybe in both senses, and had it installed. We survived our first August in Washington, with humidity regularly reading 99%.

The flip side of this was the intense cold of the Washington winter. We learnt the art of shovelling snow. I bought a heavy woollen coat and, in the fashion of the day, an astrakhan hat. The secret was to have very warm outer clothing, but light clothing underneath because of the warmth of American centrally heated homes.

The government owned two fine Georgian brick mansions and a vacant piece of woodland alongside, on Observatory Circle, a well located spot in the District, with the Admiral of the Navy living in a much grander place in the centre of the Circle. The embassy functioned in one of the mansions, and the ambassador’s residence took up the other. The vacant land is where the current purpose built embassy is now located, but in the 1960s that was just a glint in someone’s eye. During our stay the idea of actually building on the site gained some momentum, and plans for it arrived from Wellington. The ambassador, Frank Corner, dismissed them as ‘Miami modern,’ and ‘Wellington’ went back to the drawing board. Eventually the splendid Miles Warren brick building plans arrived, and the project proceeded some time after we had left.

There was a strong and stimulating team at the embassy. Ray Jermyn and Bryce Harland were, along with Frank, my seniors, and others at my level or close behind included David Caffin, John Brady and Charlotte Williams. All were External Affairs officers, complemented by a Treasury official, Cliff Terry, who as Counsellor (Economic) dealt with IMF and World Bank matters, reported on the US economy, and dealt with civil aviation negotiations. We had strong trade and defence staffs operating from different offices, a situation caused by the smallness of the embassy building — the Chancery — being no more than a large house. My office was once a dressing room, off the bedroom, which was Bryce’s office.

The backdrop to our work in the embassy was a focus on Asia. Two trends converged there. One was the decolonisation of the region after the Second World War — the Dutch had left Indonesia and for a time we had questioned whether it would turn communist; the British had departed Malaya and Singapore, and those two had been threatened by Indonesia under Konfrontasi and in Malaya’s case stressed by internal insurgency; the Americans had left Philippines, which was still searching for a stable national identity; and finally the French departed from Indo-China. How this part of the world would develop and find stability was hugely important to both New Zealand and the United States.

The second force was the Cold War and the related Sino-Soviet alliance. The impact of this was global, with perceived threats at various times in Europe, Central and South America and elsewhere, but in our time in Washington the threat of communist expansion was firmly centred on south-east Asia. Being involved in such matters in the heart of the world’s superpower was far removed from my work in Western Samoa, where the focus was entirely on the internal issues surrounding the sustainable establishment of a small Pacific Island state.

Both trends converged on the Vietnam war, which dominated the foreign policy work of the embassy. Bryce, followed later by Gerald Hensley, covered American policy in Indo-China and China and was tightly involved in liaison with the American intelligence services, a key position in the embassy. I was assigned to cover the Wellington and Washington outer periphery of the war area — Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines, which was less intensive but, in the light of the domino theory of the war (if Vietnam fell to communism the others would be likely to follow), the proximity of Indonesia as our nearest Asian neighbour, and our earlier military engagement in Malaya, still of very substantial interest.

Once during my time an assistant secretary from head office, Charles Craw, visited the embassy as part of a wider tour. He had a simple message — the heart of New Zealand’s foreign policy interests was trade, we must focus on how to improve our exports. I had no quibble that trade was important, but in the light of all these other concerns it was hard to agree that they should be pushed into a second tier. That debate surfaced again and again over the years. Prime Minister Muldoon said ‘foreign policy is trade’. But I never accepted that. New Zealand could only trade in a stable and sympathetic global environment and there were vital contributions to that to be made, besides the fact that peace and sustainable development and many other such objectives were meritorious in their own right.

And there were plenty of other tasks to share around. Mine included Eastern Europe; international communications, which was focused on the negotiations to establish an international body to manage satellite communications; representing Western Samoa’s interests; and American domestic politics. The latter was to become the dominant feature of my work, but the others all provided their moments.

In my first months Western Samoa made a request of the Americans for a dredge to deepen the harbour at Asau on Savai‘i. It needed to be a big, tough one, because the project required the removal of lava and coral rock and there was apparently nothing in the region able to tackle this. I contacted the State Department, who contacted US Aid, who contacted the Pentagon to see if there might be an army surplus dredge. Eventually a phone call came back from the State Department, saying that there did seem to be a suitable dredge at an army base in Georgia. But, my contact suggested, instead of me dealing with it through him and US Aid and the Pentagon, could I cut out all these middle men and deal direct with the Major-General in Georgia. I was given a name and a phone number.

Well, he came on the phone and with difficulty understood what I was calling about. He had never heard anything like a New Zealand accent, and I had much more difficulty understanding his broad southern drawl. After a few sentences we both burst out laughing at our mutual problem, and greatly enjoyed our discussions after that.

He, thankfully, felt very pleased that he was helping us and Samoa by finding the dredge. With some diffidence I advised him that there was no way Samoa could afford to ship the dredge to Samoa, and could he please arrange for that too? There was silence at that, then bless him, he said he’d give it a go. To my pleasant surprise he rang back a couple weeks later and said there was some navy ship going down that way — probably to American Samoa — and he had arranged for it to tow the dredge on a barge. The logistics of getting the dredge to the port, finding a barge and connecting it all to the navy vessel must have been enormous, but it all happened. The generosity and goodwill behind the US response was something not to forget, and for Samoa not to forget either, although efforts like that would have been repeated in other forms innumerable times by people helping with development assistance.

The international communications issues were more drawn out. Satellites for telecommunications were launched by the United States and administered on a private sector basis by a US firm called Comsat. But the time had come when the system needed to be administered by an international arrangement. The Americans were keen to keep maximum control, which meant that in any international governing body it wanted weighted voting proportionate to its financial input, as in the IMF and World Bank, and also private sector operational management, essentially retaining Comsat. Many other countries wanted a United Nations-type structure governed by one country-one vote, and administered also by a UN-type organisation.

In this sense the negotiations, although relating to a unique field with many specialist requirements, were a classic example of much multilateral diplomacy. It required several long conferences, usually attended by a deputy director-general of the Post Office, representing the New Zealand agency responsible for telecommunications, or at least once by the director general, with myself as the number two on the delegation and the continuity person between the conferences.

New Zealand had one of the more flexible briefs and it was clear that External Affairs in Wellington was leaving it to the Post Office to agree to whatever best suited it. In general terms we had a historic preference for the ‘one country – one vote’ tradition of the UN, but were wary of UN bureaucracies and even then could see the benefits in terms of efficiency of having business-like operations. At heart we just wanted a system that worked and was as economic as possible.

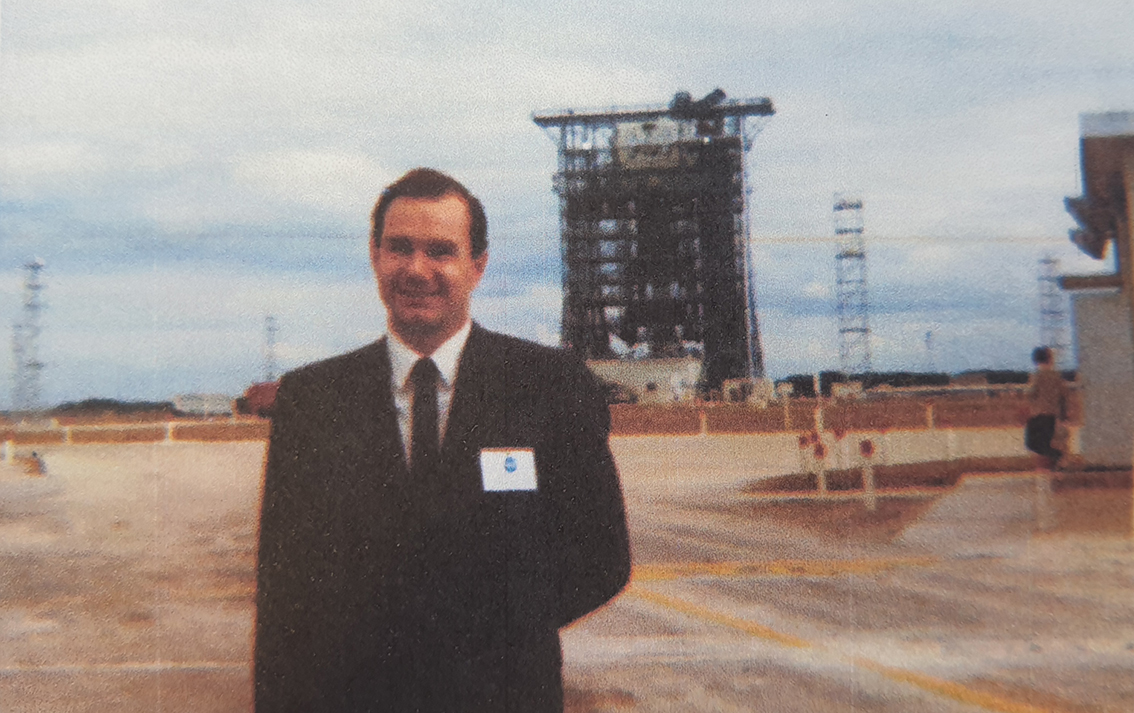

At Cape Canaveral for a communications satelite launch, 1969

We were not strongly lobbied by the US government delegation but we certainly were by Comsat, which had decided that New Zealand could play an influential role. I had ready access to all the information I could hope for. One particular benefit was an invitation to see a satellite launch at Cape Canaveral. The embassy agreed I should go, resulting in one of those experiences of a lifetime. It was at the time when ‘the race to the moon’ was at its height and an Apollo rocket was on another launch pad. The scale of everything was enormous and, if the intention was to underline that only the United States could carry out such operations, it was successful.

Eventually at the defining conference a compromise was adopted and Intelsat as the governing body with government representation was formed, with Comsat retaining much of its operational role.

As with all overseas assignments, an early task was to build a range of contacts and consolidate relationships with them. The easy way to start was with the State Department, and I called on people such as the country directors for Malaysia and my other countries, and for New Zealand and the South Pacific. They were all highly co-operative, and keen to obtain New Zealand views. They particularly valued the reports from Paul Edmonds in our embassy in Jakarta, but they had a healthy respect for all of our Asian reporting, much of which I was able to hand over to reciprocate for what they were giving me. What I most needed from them was not so much their appraisal of what was happening in the south-east Asian countries, valued as that was, but insights into American policy towards them and where the US would be heading next.

New Zealand’s involvement in the Vietnam war was an essential ingredient of our dealings with the State Department, the Department of Defence and the White House. The president in our first year, Lyndon Johnson, referred to his ‘seven fightin’ allies’ and we were one of them and benefitted hugely from that. The Economist magazine ran a story complaining — or perhaps simply observing — that Australia and New Zealand had more influence in Washington than Britain, and while I could not judge that comparatively, we certainly had wide and open access and information.

This was reinforced by our participation in ANZUS, which held an ANZUS Council meeting in Washington that I was able to attend. I must say, coming from a fairly inarticulate schooling, I was highly impressed with the fluency, knowledge, and presentation skills of the leading Americans, especially an Assistant Secretary of Defence, Mort Halperin, who led for them much of the time. The meeting was a lesson in many things — the value of international co-operation with like-minded allies, the need to know your business thoroughly, the ability to be able to think on your feet: it was high-powered company to match. Overall I thought the New Zealand delegation held its own pretty well.

There was a bit of a debate about whether we were pulling our weight in Vietnam — not in the ANZUS meeting but sometimes from American conservatives. The accusation was firmly levelled in a late-night session with an American congressman in his office. ‘You guys are so close, it’s your part of the world, you’re not doing enough …’ There was a large globe nearby so we found a long piece of cotton, put a pin in Hanoi, and measured the length needed to reach Auckland. We then swung the cotton the other way and the same length took us well into Western Europe. So the war was in their part of the world too and they were staying out.

Scoring a technical point like that may be useful at the moment to give an opponent pause but it does not change longer run thinking. In other contexts these days we would argue that we are close to and an extension of Asia, while Europe, at least in terms of world regionalism, is not. The debate in New Zealand about our Vietnam role, at that time and much later too, was usually from the position of the left saying we should not have engaged at all, that it was solely an internal struggle.

Part of the puzzle of Vietnam was the domino theory. I felt there were no certainties either way on that, unconvinced that if America stayed aside other countries would fall, or if America went in it could win and they wouldn’t fall. But I did become a little attracted to the variant theme of ‘reverse dominoes’ — that whatever the outcome in Vietnam, the resistance to communism there would buy time for the other south-east Asian countries to build their economies and capabilities to withstand communist insurgencies or other threats. Perhaps even with this distance of time it still has some credibility.

Johnson had visited New Zealand before we left, and while we were in Washington our Prime Minister Keith Holyoake paid a return visit. We were told that in Wellington Holyoake found a Texan joke for the president: ‘I hopped on a train once entering Texas, and a young man sitting beside me said, “You know this train will go all day today, all night, and all day tomorrow and it will still be in Texas.” I said back to him, “Don’t worry, young fellow, we have slow trains where I come from too”.’

He needed to find a Texan joke for the White House dinner … poor Lyndon. Twice. But for all that, to my mind Prime Minister Holyoake managed New Zealand’s engagement in Vietnam appropriately in political terms — the minimum contribution, delayed as long as possible, to keep this country fully in the loop of intelligence and strategic thinking, and our views heard.

In times of pressure, which was often, some of us went into the office on Saturday mornings. One such day Bryce came into my cubicle. ‘I’ve been talking with Frank and he wants to step up our domestic coverage. We need to build our strength to lobby congress; we need to develop a New Zealand constituency that can counter agricultural protectionism. You’re it.’

It was the best job I could imagine. I could read anything about the USA and call it work. I could talk to almost anyone in Washington and use the same cover. It meant understanding the nature of political processes and influence as these applied to trade, protectionism and foreign policy, building our linkages with businesses that exported to New Zealand as well as importers, forming relationships with a range of congressmen and congressional committee staffers, and developing some connections with the press. I found myself in an embassy car going to appointments on Capitol Hill almost as often as to Foggy Bottom, where the State Department was located, and sometimes lunching in the congressional dining room. It was decided that I should pioneer for the embassy being a member of the National Press Club, which proved to be more useful as a prestigious place to entertain non-press people than it was to meet the powerful voices of the media.

Using every avenue, including Rachel’s participation in a diplomatic/ congressional wives’ organisation, we built a range of close contacts in the senate and House of Representatives. Curiously the two we became closest to in the senate were both called Bob and both described themselves as moderate Republicans. One was the senate minority leader, Robert P Griffin of Michigan, so called because he was the Republican leader in the senate while the Democrats held the majority. He was a cheerful person, a benign listener, and rewarded me one day when I found in our letter box at home an extract from the Congressional Record — congress’s Hansard — giving a verbatim account of a debate the day before on a bill to restrict butter imports. Bob had marked his own speech: when the proponents had finished he talked about how damaging the bill would be to America’s friends and allies, with an emphasis on New Zealand. The bill progressed no further. However while the warm references to New Zealand may have been a nod in my direction, it is likely that he would have voted against the bill in any case.

He was influential to me in other ways. I asked him what he meant when describing himself as a moderate Republican. ‘Well,’ he responded, ‘I am a liberal on civil rights, and support all the legislation on that. I led a move to desegregate the exclusive Kenwood Country Club. I regard myself as a moderate on budgetary matters — I believe in a balanced budget. And I am a hawk on military matters — I support high defence expenditure to hold up our military posture around the world. So that sort of averages out as a moderate.’ It was a practical application of my growing view of how restricted it was to be locked into any particular left or right view of the world, and how a mind not too bound by ideology could be flexible and open to a variety of ideas.

Once he expressed puzzlement that the New Zealand dollar was of higher value than the US dollar. I explained that until recently New Zealand had used the British system of pounds, shillings and pence, and when we converted to a decimal system we called half a pound — ten shillings — a dollar. So in its origin it had no relationship to the US dollar, just the same name. He still had doubts, but he didn’t have to wait long before a more appropriate relationship, in his mind, came about. The New Zealand dollar steadily declined and soon fell below the value of the US dollar.

The other Bob was a freshman senator from Oregon, Robert W Packwood. He had defeated a well-known anti-war senator Wayne Morse in the 1968 elections and so came to Washington in early 1969. He could be described as a liberal as much as a moderate Republican, but for reasons different from Bob Griffin’s. Bob Packwood supported abortion — ‘pro-choice’ it was called — and ‘green’ issues related to environmental protection. In both cases their positions to some extent reflected the views of their home states, while the political system, with less rigid party-line voting than in a parliamentary democracy, was permissive of this sort of flexibility.

They were not unique. Many other political leaders at the time, such as John Lindsay, the mayor of New York, and Nelson Rockefeller, the governor of New York State, both aspirants for higher office, and others such as Senator Jacob Javits, called themselves liberal or moderate Republicans. It was a sharp contrast with today, over forty years later, when conservatism has become so dominant in the Republican Party.

Our immersion in American politics was as complete as it could be, without engaging in activities that I felt risky for a foreign diplomat. Sometimes I had to decline pressing invitations from friends like Jack Talmadge, a Washington lobbyist and general insider, who would invite me to meetings of his action groups to plan their campaigns for or against some legislative proposal or for a preferred congressional candidate. I wanted no accusations of meddling in American domestic politics, but ran as close to this as I could.

Another useful guide in our first years was Nick Johnson, a young liberal democrat and Lyndon Johnson-appointee to head the Federal Communications Bureau. I did not have much need to see him in his official capacity but he lived in the neighbourhood and presented the case for an alternative America as articulately as one could wish. But even in my first year I was concluding that putting all of his constituency together — anti-war, civil rights, consumer advocacy (he was a friend of Ralph Nader), flowerpower and the lot still would not outnumber the ‘little old lady in white tennis shoes’ that was the archetypal symbol of conservative middle America. His wife agreed! A little later came the muchhailed book, Kevin Phillips’ The Emerging Republican Majority.

Sometimes, not often, the lobbying was in reverse, and not just the argument that we should do more in Vietnam. Once a congressman from Arizona invited me to his office — he had a constituent who bred thoroughbred horses and wished to export some to New Zealand but was stymied by our quarantine requirements. The congressman, Sam Steiger, suggested that this was simply protectionism for the our horse-breeding industry, and I had to give the homily about the New Zealand economy being dependent on disease-free agriculture and horse-breeding, and so the quarantine regulations were a genuine necessity. Eventually he gave up, but the meeting would have served some purpose for him, enabling him to say to his constituent that he had pushed the New Zealand Embassy hard on the matter and they would have to see if any change could be made.

At any time the opportunity to both study and engage with the American political system would have been stimulating, but these years were exceptional. In 1988 Time magazine ran a cover article re-running 1968 as the stand-out, traumatic year for America in the twentieth century.

We were dimly aware of what we were coming to from another Time article before we left New Zealand. It argued that the US was more divided than at any other time of its modern history. We didn’t particularly believe it, but once in Washington we found the divisions palpable. At the heart of it was the opposition to the Vietnam war, and we saw the huge demonstrations on the Mall and watched on television the march on the Pentagon. Robert Kennedy became the front-running anti-war candidate for the 1968 elections and was assassinated; Senator Gene McCarthy took over his mantle within the Democratic Party.

One night, getting ready for bed after a dinner party for Washington officials, Rachel said to me, ‘Lyndon Johnson isn’t going to run again.’ I looked at her with some disbelief. It was Washington custom for the men after dinner to retire to a den or lounge for their brandy and cigars, while the women went upstairs to the master bedroom to ‘powder their faces’. It was always worthwhile swapping notes later to see who had picked up the best gossip, and that night Rachel was the clear winner. A week or so later the president did indeed announce his retirement. Not that I always told her my ‘gossip’ — if sensitive information came to me she wisely didn’t want to hear it.

All through 1968 the Vietnam war issue ran hot. Hubert Humphrey became the Democratic Party’s establishment candidate, but Gene McCarthy continued to gain in strength. I was assigned to go to the Democrats’ convention in Chicago where the choice was to be finalised, and the high drama continued there. Massive demonstrations of mainly young people filled the streets in support of McCarthy — ‘Clean for Gene’ was the slogan — and the police moved in to break them up. Inside the convention hall, famous men such as Adlai Stevenson and Hubert Humphrey rose and spoke, but around the walls were television monitors showing the battles outside, and the eyes of the audience were fixed on these. The tension was real, but the establishment candidate Humphrey was nominated.

About a month later I went to Miami for the Republican convention. There was no strong alternative to Richard Nixon. The most memorable features were the intensity of American patriotism with the flags, banners, balloons and music of this mood prevailing everywhere, and, by the main entrance to the Convention Hall, and no doubt funded by the Democrats, a very pregnant black woman sitting on the pavement holding the Republican Party’s slogan of the moment, ‘Nixon’s the one’. There was not much doubt through the campaign that followed that Richard Nixon would be the next president of the United States.

A second tumultuous change was tearing at the United States during this time, the civil rights movement. Before we left Wellington it had produced the rioting and burning of Watts, Los Angeles. During our first year in Washington it produced its assassinated martyr, Martin Luther King. The weekend of that I had gone to attend a conference on the American Constitution in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was making my way back on a Greyhound bus. After rioting broke out around 16th Street in protest at the killing, a curfew was placed on much of the District of Columbia. Somewhat surprisingly, the bus was allowed to enter the curfew zone to get to its depot.

I made sure I was one of the first people to exit the bus, and to get into one of about five taxis by the terminal. The ride was through a terror film set. In all directions the streets and avenues of Washington were eerily deserted except for clusters of three soldiers on each corner. Occasionally army trucks rolled by crammed with soldiers all with bayonets unsheathed on their rifles. Three times the taxi was stopped and we were threatened with instant imprisonment for violating the curfew; each time the driver fasttalked our way out by claiming I had diplomatic immunity and getting me to wave my red diplomatic passport as evidence.

Pictures of a pall of black smoke pressing down over the city flashed around the world, prompting plenty of inquiries from New Zealand about our safety. The reality was that only a few blocks burned and in the totality of greater Washington it made little difference to most lives. Certainly in our suburbs the mood was nonchalant, as many residents rarely went near the central city anyway.

It was suggested that I should draft a ‘think-piece’ about the nature of the civil rights movement and where it was all going. Usually the staff set our own priorities for reporting in our respective fields. It was one of the most sustained and demanding tasks of my time there. I started with the magnum opus of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The American Dilemma, and then much else, but ended up with a coherent 20 pages. The embassy’s consensus was that the movement fitted the ‘Revolution of Rising Expectations’ theory of such movements: the truly oppressed are too busy surviving to rebel; it is only after they start to climb the socio-economic ladder that their challenges to authority gained real strength.

There was a third revolution of sorts also gripping the United States at the time. It was a rethinking of society at a fairly intellectual level relating to the role of authority and capitalism, reflected most dramatically in the students storming the offices of university deans and taking other radical action across the country. The National Guard was called out to maintain order in some situations, leading to the deaths of four students at Kent State University in 1970. This movement was international, with student rebellion in Paris and elsewhere reflecting a similar push for change. It combined with a new mood of non-conformity expressed in music — as at Woodstock; in sexual freedom — where its slogan ‘make love not war’ showed its alliance with the anti-war movement; in flowerpower and in communes and the like.

But it had a sharp edge too. Combined with elements of the civil rights and anti-war movements, it took on a revolutionary rhetoric reflected in the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Army and the Weather Underground (‘Weathermen’), with radical leaders like Eldridge Cleaver and Timothy Leary. While these always needed to be taken seriously in a policing, law and order sense, they were in the wider context of America always containable rather than seriously threatening. A number of analysts saw the Nixon election as Middle America’s response to this complex movement in particular, although these days decades later this is seen more of a response to the cold war.

Yet another troubling element was the fear of nuclear attack. Americans had built underground shelters and kept stockpiles of food and other necessities. At social events we were quite often asked about how to migrate to New Zealand, to escape such threats. I had no role in dealing with formal requests to migrate, but always told casual inquirers that they should visit New Zealand first before taking any steps to shift. New Zealand might indeed be a relative safe haven but it seemed to me that most Americans I met would find a New Zealand town and lifestyle, as in the 1960s, difficult to adjust to.

One of many asides was an invitation to speak at a New Jersey university about New Zealand as part of a 12-part lecture series on Australia and New Zealand. Six lectures on Australia had been completed; I was the first on New Zealand. Since many Americans thought that New Zealand was just off the coast of Australia and not too different, I gave an opening burst, taking a fair bit of latitude, on just how different they were from each other: Australia was a continent, New Zealand was islands; Australia was flat, New Zealand was mountainous; Australia was dry, New Zealand was wet; Australia was red/brown, New Zealand was green. But then said some other more careful things. I have had occasion later, in Canberra, to contemplate how complex are the differences and similarities between these two countries.

Back to Washington. We had a dinner party in January 1969, in the dying days of the Democratic administration. Because of the American system of filling at least the top four layers of each government department with political appointees, our guests could talk of little else except about their next jobs. An Assistant Secretary of Transport said he had an offer of Professor of Transportation Economics at the University of Georgia, but was holding out for a similar position closer to Washington, at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and that sort of thing. It was good reinforcement of the functioning of the American system of interchanging positions between government, academia and the private sector. At that time I was a warm admirer of the system, but these days I am not so sure. Both their approach and our New Zealand system of career, neutral public servants filling the senior positions have finely balanced merits.

From February on, the receptions and dinners were replete with young Republicans, an amazing percentage of them with crewcuts and from California, all Bob Haldeman look-alikes, he of later Watergate infamy. They redefined clean cut to a new plateau, all determined that the world was going to change, and for the better, because of their efforts. I have heard that story a few times since, from different new governments in different countries.

Dinner parties were invariably interesting. Because of a trade embargo, Americans could not access Havana cigars from Cuba, but all the embassies used their diplomatic privilege to do so. One night a young lawyer from a prominent lobbying firm took such a cigar, all encased in a sealed metal tube, that I offered him but put it in his pocket unopened. The next day at his office he showed his boss, ‘Look what I’ve got!’ The boss similarly put it in his pocket, unopened, and later that day was talking to one of his mates on Capitol Hill, a Senator Dick Russell from Georgia. The politician did not follow suit — his deprivation was such that he wrenched it open and blissfully started puffing.

The next day a slightly embarrassed young lawyer phoned at the office. ‘My firm represents Dunhills in the United States. I wonder this: if you would give me the rest of the Havanas in your box — I’ll take pot luck on the number — I’ll give you a full box of the best Dunhills.’ I could see no diplomatic incident arising from this and agreed to get back to him the next day. I counted about nine cigars left in the box, brought it into the office and arranged an assignation to make the transfer.

The first three years of the Nixon Administration occupied the majority of our four and a half years in Washington. The social mood slowly settled, until it erupted in a totally different form, not long after we had left, with Watergate. In foreign policy Nixon was able, as a leader whose conservative credentials could not be challenged, to negotiate a form of settlement to the Vietnam war, start a dialogue with China (invariably referred to as ‘Communist China’) and negotiate a strategic arms limitations agreement with the Soviet Union.

After his unilateral announcement of the withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam, Nixon engaged in a number of variants including the bombing of Viet Cong logistic routes through Cambodia, which caused an outcry because it seemed at variance with the stated policy. But a senior New York Times columnist, James Reston, wrote with insight that in foreign affairs a policy direction does not always mean a straight line. He talked of zig-zags, and the need to see the underlying trend line in a policy. It was entirely plausible: Nixon had never said he was going to withdraw in a manner that left his flank unprotected and just walk away with nothing. It was a rich observation into the administration’s Vietnam policy, not that we weren’t fully briefed. But it was also a useful observation with wide applications, from the share market to, much later, climate change, to the decline of violence in Western societies and many broad trends. They have reversals along the way and we must look past them to the longer term.

A major event in this realignment of American foreign policy was Nixon’s Guam Doctrine statement, delivered on the island of that name while he was en route to Asia in mid-1969. It reflected America’s weariness with the Vietnam war and stated that in future wars in Asia, any Asian allies under attack and not the USA should provide the ground troops. The US would help but not in the front line. It was not just mealy-mouthed backsliding: this new policy was accompanied by a vigorous assertion of America’s commitment to its alliances with Asian countries by means of the nuclear shield, which was intended to provide both a deterrent and an awesome response if cause were given.

It caused a stir but had its logic. After all some of the east Asian countries — the ‘tigers’ — by then had some capacity to look after themselves militarily, except from a major attack from China or the Soviet Union, and the US not only wanted to withdraw from Vietnam but avoid any other such entanglement. Clearly the domino theory was abandoned, but in any case the countries had developed a capacity to deal with insurgency. The religious insurgency or terrorism of recent times is another story.

While all this was going on our two boys were enrolled at school, and sang ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ every morning. We bought a round, above-the-ground swimming pool, big enough for an adult to get three strokes in from side to side, and certainly big enough for children to learn to swim in. Later it was off to the Seven Oaks pool where they both acquired a high level of swimming skill. We acquired two gerbils as pets. They were meant to be well locked in a cage when not held or played with, but somehow managed to escape from time to time. We found they had a particular liking for gnawing through telephone wires.

We watched on live television Neil Armstrong making the first moon landing. Winning the space race was part of the gel holding America together in the face of its severe social and political differences. The two boys and I joined Indian Guides, a father-and-son affair that met in each other’s houses one evening once a fortnight or month, and sometimes for other activities. Nick Johnson was part of this group. Its outings illustrated some of the subtleties of cultural differences. The group decided on a Saturday walk up the Potomac River. Knowing the affluence of the neighbourhood and the dressy casual clothes they wore to the evening meetings, I put on some reasonably decent walking attire. I was way out of line, the other dads coming dressed in the most knocked-about sneakers and jeans and old sweaters of a sort I didn’t actually possess.

The next time a similar outing was proposed I came prepared to conform, only to find them dressed exactly as I had expected the first time. I was the bum of the group. It didn’t matter, but I swear they did not co-ordinate, that there was just some difference between the two events that I could not perceive which led those with local knowledge to know the appropriate dress.

Once we went for a weekend overnight camp. It was a great way, through boys’ games and barbeques, to get to know a wide cross-section of informed Americans, as well as our own offspring. I still recall one drawn-out campfire story about an Indian Chief of long ago, called Falling Rock, who went missing, but the search for him continues even to this day with signs saying, Watch out for Falling Rock.

Holiday time was top-flight. From a departing British diplomat we bought a campervan, which was a fold-up tent mounted on a trailer. When travelling it had the great advantage of sitting low behind the car, unlike a caravan, but when opened up it had a double bed at each end, one for the two boys and one for Rachel and me, with cooking and seating space in the middle and room for a cot for Gillian.

Once we drove south through the Carolinas, paddling between the moss-laden trees on the forested black swamp of North Carolina, fishing on the Outer Banks and Cape Hatteras, and exploring Florida as far as the southern islands of Key West. Another time we drove up the east coast through Boston to New England to see the fall colours, and on to Quebec. We were playing frisbee in a campsite near Quebec City when the campervan nearest to ours began to rock rhythmically. I quickly threw the frisbee as far away as I could and our game continued at a soundproofed distance from the strongly swaying campervan.

One year we decided we had enough leave for a full month instead of my usual few days at a time or two weeks’ holiday, and set out across the United States. We took a slightly southern route through West Virginia, Kentucky and eventually across the panhandle of Texas. We were amazed at the American campsites: the site for our camper and car was normally a bay marked by trees on three sides so that it was hard to see the camper in the next bay. There was a fireplace with chopped wood beside it. Part some leaves on a tree and there was an electric socket. The weather was warm and many spots, with a bit of careful selection, had a swimming hole or a pool. It was idyllic. All the same, every third or fourth night we would move into a Holiday Inn or similar, and have baths and watch television.

America itself was stunningly attractive and I couldn’t help think of the people who thought it an industrial, polluted mess. We arrived in Arizona at a reasonably high altitude and set out to drive down to Phoenix. The temperature there was forecast to be 112˚F (44˚C) and we were feeling scared about that. But we had to stop on the way, alongside the first giant suawaro cactus that we saw. Geoffrey had recently studied them at school, and was told that if you tooted your horn loudly the birds that nested in the cactus would fly out. We tooted in vain, as no doubt had hundreds of cars a day for 30 years. We saw the meteor crater in Arizona, the Indian pueblos in New Mexico, then headed north through the badlands to Colorado, Pikes Peak and the Grand Tetons, then east through the corn country of the mid-West, none of us wanting to get back to home and normalcy.

It was 1971 and we had been in Washington for over four years. We increasingly felt we should get back to our roots, or else we would be applying for residency in the US. The time came to go and we had a wonderful round of farewell parties with some genuinely sad good-byes. We decided on one last adventure. We flew to Chicago, which we had not seen except for my convention trip, and explored its marvellous museums, art galleries, skyscrapers and river, then flew to Seattle on one of the early flights of the 747 jumbo jets. There we were taken to explore the amazing Boeing Exploring the vast USA was a feature of living in Washington — Pike’s Home and abroad, Wellington and Washington factory where the 747s were made. Then with a rented car we drove in leisurely fashion down the west coast to San Francisco and on to Santa Monica and Los Angeles.

An Air New Zealand flight took us home across the Pacific. It took off from Honolulu at midnight on the start of Geoffrey’s birthday, the hostesses brought him a birthday cake, and then the captain said we should all put our watches on to the next day — a one hour birthday.

< Back to USA overview