TOURISM: MARKETING

From chapter 10 of the memoir Compass PointsIt is March 1980. The phone rang when we were back in Rutland Way in Wellington, and I was busy painting and gardening and the like after our years away in Canberra, enjoying the two weeks or so before I was due to start my new job. It was the Assistant General Manager of the Tourist and Publicity Department (NZTP), Tony Shrimpton, wanting to call and meet me. I felt there was no need, I was happy to come in on the assigned day, 1 April, cold turkey. He persisted...and I had to agree. But I didn’t wash all the paint off for the occasion. He was a pleasant and competent person, a good augury. I can remember only one question, “What are you planning to do on your first day?” and my response, “Oh I’ll probably just rearrange the pictures on the walls.” I had some sense of what would be involved in taking over a large government department, and did not need to anticipate it before time.

But my response caused a stir - there were no pictures on the wall to rearrange. With some scrambling around, I was later told, paintings of New Zealand scenes and Maori faces on black velvet, purchased at the insistence of a previous Minister, were found in a cupboard and placed one on each wall of the General Manager’s office. Nothing could be more certain to ensure that I did indeed re-arrange the paintings on my first day. I took a lunch break and walked to a dealer gallery which specialised in prints and bought three or four by Gary Tricker, Barry Cleavin and others, a bit whimsical but well regarded in the art world at that time. They were much studied like entrails, to give insight into this new boss.

I enjoyed my first day, and the many that followed, learning about the institution that I had inherited. I met a co-operative deputy Bing Haase, who mainly looked after the corporate side – finance, staffing, buildings, land and the like. The rest of the department had a tourism division under Tony with two main branches, and a separate publicity side with three divisions, each reporting directly to me.

One of Tony’s branches promoted New Zealand overseas to bring more visitors to the country – “inbound tourism”, and sometimes promoted within New Zealand to encourage residents to holiday here rather than go overseas – “domestic tourism”. This was the Department’s big spender. The other branch under him ran the chain of Government Tourist Bureaus (GTBs), which were offices somewhat like travel agencies, in the main New Zealand cities and several overseas places in Australia, the United States and London, and which provided specific information about New Zealand tourist products and made bookings – that is, they sold travel product. They also ran a coach tour operation Tiki Tours, and some tourism operations such as the Waimungu Round Trip at Rotorua, where these were on land the Department owned. There were also under Tony two or three persons dealing with tourism research and issues relating to the development of tourism around the country.

One of the publicity divisions was the National Film Unit, ensconced in a special purpose building in Lower Hutt, which made its own films, made films for others under contract and processed films in its laboratories. Then we had the National Publicity Studios, which specialised in photography, static displays and the like. If you walk past the Old Government wooden building on Lambton Quay you can see a large carved New Zealand crest on the high point of the roof: that was made at the NPS in the 1980s. And thirdly, on the publicity side, we had the Information and Press Services Division (IPSD) which comprised experienced journalists and writers on secondment to other departments and Ministers’ offices to prepare press announcements, speeches and other written publicity material. All three had quite strong national reputations in their fields, but I soon felt all were under stress relating to new technologies, changing market conditions and new government demands on their funding.

At the National Film Unit, 1983: Neil Plimmer with former producer Cyril Morton - holding the same camera he is seen using in the photo at rear, shooting travelogues in the early 2020s - and NFU executive director Doug Eckhoff.

For the tourism side I reported to a Minister of Tourism; for the publicity divisions to the Minister in Charge of Publicity, invariably two different people. Between the two arms the Department at its peak had a staff of around 620, an annual budget of $100 million and 14 offices around the world and throughout New Zealand.

The organisation did not last in this form, initially because of my restructurings, later because of Cabinet imposed changes.

I spent a few months talking to staff and industry people. I was asked to speak at industry functions and know that these first efforts were not highly successful, since I talked to speech notes prepared for me structured around some aspect of the department’s interests. With hindsight I should have spoken more just from the heart, and let the audience get a better feel of who I was and where I might be going with tourism. But everyone was positive and I became increasingly engaged with the position and its potential.

It was a minor part of that that I was not feeling symptoms of loss from my old department. The tourism staff overseas were closely aligned with our diplomatic offices and there was plenty of shared interest between the two agencies. And one day after just three weeks into the job Matt Ramsden, a General Manager at Air New Zealand, rang to say would I please come to a meeting in Auckland of the New Zealand Chapter of an organisation called the Pacific Area Travel Association (PATA) and be elected its chairman. I demurred: why would they elect someone they had never met? Oh they will, said Matt, they like having the head of the Tourist Department as Chair. I decided to go to meet them and was duly elected, but the point here is that when I saw the agenda it looked just like an FAO Council agenda: membership dues, voting powers, budget allocations and so on. In some respects I had not moved far.

I had to start with tourism growth. The economy needed it. It was what Parliament voted most of our money for. I felt I had inherited a reasonable base to work from – committed staff but not all pointed in the right direction. It was not too difficult to determine what needed to be done. The division that dealt with promotions had to understand and adopt the skills and language of marketing, and become the most sophisticated government-funded tourism marketing agency in the world. At that time the Irish and Hong Kong Tourism Boards were probably the best regarded in this respect. I was determined we would match and then outstrip them.

I immersed myself in the subject, reading in the evenings every recommended book and article on marketing and tourism marketing that I could, over my first year or two in the job. The premise as articulated at the time was straight-forward enough: promotion and selling, the old approach, was taking your product and generating as many sales as you could through various promotional techniques; marketing, our new look, was knowing what the customers wanted and setting out to provide it.

After six months I felt ready to move. When I briefed the State Services Commission (which was my employer then) they were so supportive that they found and contracted to the department a marketing specialist Peter (“It’s the sizzle not the sausage”) Wakelin to help develop the staff capability in this area. I briefed the Minister Warren Cooper and he was happy, but maybe a bit bemused too, willing to give me my head but probably not much convinced that words and re-organisations would make a huge difference. Warren had a background as a commercial sign writer and then motel owner, and was street wise and politically savvy and I fully respected his views.

And so in late 1980 many of the staff found themselves working in a new Marketing Division. They were to engage in most of the components of a marketing mix including identifying the population segments overseas most likely to travel to New Zealand; identifying the product needs of those potential tourists; designing comprehensive market activity including promotions, trade education, public relations, print, radio and television advertising and direct mail; and feedback, research and review. In the full marketing mix it was only fixing commercial prices that we could not do.

To pursue this direction we needed a research capability, which required new staff and was expensive since research into our overseas markets required contracting overseas firms. To avoid this in the first years we partnered with the San Francisco-based PATA, which offered market reports to its member countries, and which we were able to influence to ensure its studies covered the questions of most interest to us. By the mid-eighties we were commissioning our own, and had built the capability to direct this research, interpret it for our own marketing plans and explain it to the industry so that as many companies as possible benefitted from it.

Market research in the early 1980s was particularly designed to identify population segments normally defined in social and economic terms: affluence, education, age and geographic location being the main criteria. They permitted targeted marketing to states, cities, readers of particular magazines and so forth. Much of the time this was fairly straightforward. In both Japan and the United States, for example, the main segments, initially, were the retired markets - in Japan (the “silver market”) because younger working markets did not feel they could leave their work for long enough holidays to visit New Zealand; and in the United States (the “blue rinse market”) because younger workers did not have long enough holiday entitlements. The early eighties were still the time of a big annual holiday rather than a variety of short breaks.

But our research showed that established patterns were eroding. The tourism consumer proved to be a moving target varying greatly over time and with country both in terms of who they were and what they were looking for. In Japan a honeymoon market was soon identified, then later the “single office ladies”, then “full mooners” (whose children had left home so that they could take a sort of second honeymoon), and later still a variety of specialised segments including school excursions.

In Britain our target audience was defined as persons with existing contacts in New Zealand – the Visiting Friends and Relatives (VFR) market. There was reason for this: it was accessible through clubs and similar groups in the larger cities, and it had provided a productive flow of visitors for years, while the British holiday market had little record of travelling to the other side of the world – it was short- (to Europe) or medium- (to North America) haul. But on my first visit to London in the job I was given a presentation by our advertising agency which graphed the static nature of VFR travel from Britain, as a percentage of total British outbound, and showed the steady growth in recent years of the overseas holiday segment and its growing propensity for long-haul travel. In other words with VFR we were locking ourselves into a no-growth segment. Our strategy was rapidly overhauled and the rest of the eighties showed a strong shift to marketing New Zealand holidays independently of VFR, and of success in that.

I was personally concerned that our own work had not disclosed this shifting potential but it was early days in the development of our research capability and, I believe, the last time that we needed an outside agency to tell us about such a significant development.

A different challenge came with a new approach to defining the target segments. By 1982/83 the Department commenced intensive examination of the role that psychographic segmentation might play, partly stimulated by the work of the Henshall reports on New Zealand tourism commissioned by the Tourist Industry Federation (TIF).

The work at Stanford University which underpinned this approach divided populations into three main categories, Outer-directed, Inner-directed, and Needs-driven people. Henshall particularly identified a strong trend in developed countries for people to become more inner-directed - that is, individualistic, or internally driven, reflected particularly in the young “I am me” generation – as opposed to a more conforming, externally-driven “keeping up with the Joneses” approach to life. The inner-directed crowd had grown from a tiny number in the U.S. population in the 1960s to over a fifth by 1980, and was forecast to grow more rapidly in the years ahead. These inner-directed people could come from any of the traditional socio-economic population groups – old or young, rich or poor, married or single. The theory that flowed from this was that a population should be segmented for marketing purposes according to personality types, their lifestyle choices and buying motivations, not by age, income and so forth.

And so we started talking about adventure seekers, achievers, the societally conscious, and so on. For example a 1984 study identified our likely Australian segments as “New Enthusiasts” and the “New Indulgers”, a 1988 study identified in the British market the various needs of “Cultural Adventurers”, “Relaxed Recreationists” and so on.

It needs to be said though that psychographic segments were less easy to reach. Our United States advertising agency, deeply immersed in this debate with other, bigger clients, was by the mid ‘80s becoming disenchanted. “You identify your segment as people who like warm fuzzies and buy teddy-bears, but how do you market to such people efficiently?” they asked in frustration. On the other hand, traditional socio-economic segmentation which included demographics permitted highly targeted marketing. We were able to narrow the states targeted in the U.S. down to 12, or four, as we wished, and then to cities. David Chapman, our Senior Travel Commissioner in the United States for some years commented, “We can get it down to street numbers, if we are willing to pay.” I noted with interest that in the 2016 American election campaign, marketers are claiming they can “get down to individuals if the politician is willing to pay.”

There were frequent issues over translating our research into marketing strategies. I felt a need to ensure a reasonably realistic relationship between the marketing messages and the products we were offering. I disliked over-pitched promotional claims and once vetoed an ad agency’s pitch based on New Zealand as Paradise. I declined proposals that we should, because Asian travellers were looking for shopping, promote the country as a shoppers’ heaven. This notion of not over-selling has a sound basis in marketing theory, and did not prevent us from putting “sizzle on the sausage”. New Zealand could easily and realistically be fun, refreshing, and have a host of other emotional attributes attached to its core appeal without resorting to false exaggeration.

In 1980, the heart of New Zealand’s tourism image seemed clear, and lay with the diversity of New Zealand’s natural scenery. We offered a great variety in a compressed and manageable land area. Decades of promoting this in various guises had certainly had its effect. In the mid-80s the Trade Development Board undertook research in the United States to ascertain American perceptions of New Zealand. Notions that New Zealand was a developed country, a western democracy, a wartime ally or a great agricultural exporter featured hardly at all: the predominant image was simply the tourist image of a “mighty pretty country.”

A great example of this diversity image was the advertising campaign I inherited in the United States in 1980: “New Zealand the world in one country” which incorporated an imaginative map showing Norway, Hawaii and other unrelated places joined together with a text along the lines of, “the fjords of Norway, the beaches of Hawaii…” We had them all. It was hugely successful and we left it in place for another two years. But around 1983 the time came to shift from promoting ourselves by comparison with other countries to a free-standing projection of New Zealand.

Once I felt nailed in the debate about the images of New Zealand to be projected. An airline new to New Zealand’s skies, Cathay Pacific, said it wished to produce one poster on New Zealand, for global use. Each of its destination countries had a poster with a symbolic image: the Eiffel Tower for France, tulips with a windmill for Holland, and so on; what was the equivalent for New Zealand? Well, what was (and is) it? - Mt Cook, Pohutu Geyser, a Maori concert party? The issue was less of a problem when the variety of the country’s attractions could be set out, as we usually did by showing multiple images; it loomed larger when it required extreme simplification.

It was central to the Department’s thinking that we had themes and images tailored to each market, being a country or a related group of countries. Our research affirmed that what the potential visitors were looking for varied too much to use a common approach across major markets. The Tourism Board as the department’s successor adopted the same approach throughout the 1990s, until in 1999 it approved the policy of one theme for all markets – “New Zealand 100% Pure.” This was a significant decision which may say something about the convergence of tourism markets in the age of globalisation but which certainly offered great savings through economies of scale and the strengthened branding of New Zealand as a destination. It has been a great success, although we of course will never know if more or fewer tourists would have been attracted by a market-tailored approach.

It also became clear that for many overseas visitors our “man-made” landscape – what the troops called “green rolling sheep” – was as much an attraction as mountains, lakes and geothermal features, and offered plenty of scope to be integrated into the promotion of scenery. The popular concept of “clean and green” encompassed both farmland and natural scenery.

We learned too that visitors were strongly interested in our way of life, especially in the secondary towns and rural communities. This lifestyle was thought by Americans in particular to be evocative of life as it had been in the 1950s, an age of nostalgic memories centring on stability and family values. A friend overseas, Ken Chamberlain the head of PATA, who had regular opportunity to visit New Zealand, wrote thoughtfully about relating this image to one of establishing a “New Zealand personality”, suggesting that it might be best captured by a tall, rugged, avuncular (white male) farmer – a bit like Ed Hillary I suppose – holding a lamb.

Some American studies showed that most people in developed countries had a mental shortlist of about three destinations they wished to visit. The list was built up by many influences and over time, and came to be popularly known as “the bucket list.” Most holiday decisions came from choosing which of those three an individual would go to next. So tourism destination marketing would logically be targeted at getting one’s destination on as many people’s bucket list of three as possible, and then the more specific and commercial marketing would be aimed at getting them to choose your destination and product next.

If one word summed up the change in tourists’ expectations in the 1980s it is probably “choice”. Over the decade the ‘one product (a coach tour of both islands) fits all’ rapidly declined and the demand for variety and new products steadily increased. This profound shift from group tours to “free and independent travel” (FIT) was one of the major challenges of the 1980s. Group coach touring was the backbone of New Zealand tourism in the 1970s, with investment in coaches, in motels and motor inns and in sales networks all geared to this. The shift to FIT was of course a practical manifestation of the changes in society towards inner-directedness in attitudes and travel, and the wish to make one’s own choices.

One of its features was the growth of backpacking, but FIT was not confined to young people nor to “downmarket” products. Plenty of older visitors started to prefer self-drive touring to a packaged coach experience and in varying degrees the growth of FIT affected all segments from all markets. The most direct product upshot was the growth of rented camper vans and rental cars, and of related air/accommodation/transport packages, such as “fly/drive” promotions. Investment in camping grounds grew. There was plenty of money to be made by people riding this wave at an early stage, especially in the booming new campervan market, and also disappointments, such as the inability of scheduled buses and rail to capture a growing share of the FIT market.

It is an aside to this that on an early tourism trip to the United States I asked the Los Angeles representative of a major New Zealand coach and tour company if he had made any changes to his product over the past year to meet these changing consumer needs. He firmly said yes, and then described changes that he had made to the design of his brochure. I thought this a nice case of Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message,” but it does show the understandable perspective of a salesman towards his sales tools and on the information needs of his direct clients, in this case the American travel agents.

Then we found that people were seeking more active and participatory holidays, rather than the passive viewing of sights. Our images responded – in a couple of cases a bit slowly – by replacing the visual images of pure, spectacular scenery with those with people in them enjoying and participating in their surroundings or outdoors activities. A decade or so later the term “interactive tourist” reinforced this theme of participation.

Another major shift we faced was in the tourism distribution chain. In my first year or two, marketing in many countries was pursued on the notion that tourists normally made their holiday bookings on the advice of their travel agent – rather as they made their investment decisions on the advice of their investment manager. It followed that a great deal of effort was placed on travel agent knowledge and awareness. The travel trade was a key focus of marketing efforts in Australia, North America, Japan and Europe. They were visited on their home patches by our representatives and shown the latest about New Zealand and how to sell it, and they were brought in groups for familiarisation tours of New Zealand.

But travellers were increasingly confident of making their own decisions and by late in the decade many were turning to a travel agent only to finalise an actual booking. And so awareness raising and motivating had to shift from the agents to the consumers directly. Travel show participation was reduced, unless these had a high consumer rather than a trade audience, and advertising in magazines and newspapers with high readership in our targeted audiences increased. Familiarisation trips to New Zealand comprised of fewer travel agents and more of travel writers from consumer magazines.

This shift permitted significant office savings abroad - a media/consumer focused marketing approach was better managed centrally. Later in the decade I could close the offices in New York and San Francisco in favour of consolidation in Los Angeles; in Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne and Brisbane in favour of Sydney; and in Osaka to Tokyo.

Television was a special challenge. Over the decade it was used increasingly in Australia where the main city markets were targeted, and periodically in the USA, also focused on selected states and cities. There was no doubt of the merit of television advertising in raising the profile of the destination, but research measuring “conversion” to actual travel to New Zealand was less clear about its merits, especially given it expense.

New Zealand’s weather caused the unavoidable problem of seasonality with most of the tourists coming in summer. Compared with year-round destinations, this was a severe drawback: it was much more difficult to get a good return on investment when plant was being well utilized for only about four or five months of the year, and the commercial need to off-set the winter low season by high pricing in the peak season did not always support the country’s reputation as a “value for money” destination.

We set out to address this around 1982/83, with a strategy based on three elements: we would promote shoulder and off-season travel to New Zealand in countries where the New Zealand winter seemed relatively benign; we would develop and market New Zealand as a winter sports destination; and we would develop and promote a wider range of all-weather facilities such as museums, conference centres, heritage buildings and the like.

After review, Japan was targeted as the first market for general winter travel. A group of Japanese travel agents was brought out to tour during winter, with some emphasis on the West Coast of the South Island given this region’s reputation for mild winter weather. Their report was better than we could have wished, and momentum was developed from that. In most markets the focus was on the shoulder season rather than the real depths of winter.

The winter sports theme had an obvious uptake with skiing. We made a sustained effort to attract more Australian skiers, including the organization of ski shows in Australia jointly with the New Zealand ski industry, but it became clear that an active ski marketing campaign needed to be supported by more appropriate product at home. As early as 1982 Don Hayman, our new Director of Development and a competent skier, attended a course in France to understand tourism and ski field development in mountain areas, to build this into the Department’s and the industry’s planning. It became clear that in Australia our weakest point was the inability to guarantee snow, and that this factor would weaken the results of our efforts in other markets too.

Hence it became a priority to talk to the major ski field operators about the need for snow making, but I was repeatedly told that the conditions were not right for this in New Zealand – the equipment required vast amounts of water which was not available, just the right temperatures, high capital investment not justified by the numbers and so on. The break through happened when a small operator at the top of the South Island, Rainbow Skifields, took the plunge. There was great elation in my office when we were told of this. We were determined to assist the company to ensure that it worked. It was very soon after that the big players, Mt Hutt and Coronet Peak, suddenly found that snow making was not impossible after all, and we were away.

To be more widely successful, we needed to win better global recognition for New Zealand’s skiing capability, which meant bringing out specialist ski writers to visit. We worked hard with other organizations to attract the national ski teams of major skiing countries to use New Zealand as their off-season (northern summer) training ground, with some success at the expense of our main rival Chile. Later in the decade we felt the industry was ready to host international ski events. I did not support a Canterbury group arguing for a bid for the Winter Olympics, but we did go for the more manageable, and very prestigious, FSI championships. Don led a small industry delegation to the international ski industry’s annual meeting in Turkey to make a bid, armed with much sophisticated support material – and succeeded. The first FSI in New Zealand was held at Mt Hutt the following year.

The business of attracting conventions and meetings to New Zealand was a strategy in its own right as well as being part of off-setting seasonality. The visitors at these were high spenders, and if they came in winter so much the better. The private sector mainly through a few hotels was active in various disparate ways but a national strategy with a lead organization was lacking. In terms of involving the industry a first step was to convene a major meeting in 1982 with relevant businesses from across the country to set an agreed framework. I asked Sue Caldwell, who had achieved great success in this field in Melbourne, and whom I had met in PATA, to come over and provide some inspiration – which she did. I asked Gowan Patten to drive the follow-up from within the Department, even to the extent of drafting a constitution for a New Zealand Convention Association - which he did.

We launched a major campaign the following year. Departmental officers were assigned to key overseas posts, particularly the United States, to specialize in generating conference business and David Brooker was appointed to mastermind the effort from Wellington. At the Association’s annual conference, Gowan was elected President and David appointed Secretary. Marketing tools including brochures on conference facilities and slide sets to support presentations were prepared. A data-base was developed and a research programme started to identify needs and economic impacts. The battle to get the customs and statistics departments to include conference attendance as a purpose of visit on the arrivals card was drawn out but eventually won.

The intention as always was that the industry, as soon as its capacity developed, should take over a larger role. This happened in time with private sector appointments to the President and CEO positions at the Association. But this segment remained embedded in the Department’s marketing activities thereafter, with great benefit to the country.

We pinned to an office wall a large graph of visitor arrivals by month, to measure the effect of the strategy to reduce seasonality. It showed peaks on each side, representing January/February and December, and the winter trough through the middle. For three or four years the pattern was marked on it to see if the trough reduced relative to the peaks. It did.

We had to improve the resilience of the industry by reducing its dependence on one or two key markets. In 1980 nearly half of our arrivals came from Australia. The need to diversify became the theme of a number of my early speeches to the industry, drawing the analogy with the decisions of our agricultural exporters in the previous decade to reduce their dependence on the U.K. market.

We targeted Japan as the Asian market with the greatest potential, West Germany among the Europeans, and, with rather less emphasis, Canada as a likely additional source from the Americas. The Department had wisely opened offices in both Tokyo and Frankfurt in 1972, headed by particularly able people fluent in the local languages, David Lynch and Brian Duncan respectively. Growth had been steady but not spectacular through the seventies but Japan in particular delivered for the first half of the ‘80s – Japanese official statistics showed that New Zealand was the fastest growing destination for Japanese overseas travel in the period 1981 – 86.

With ambassador Graham Ansell (left) and an interpreter with city and industry leaders at Utsunomiya, December 1983 - visits to Japan were always rewarding.

Because of this I visited Japan more than any of our other markets, although there were cultural and other reasons for this. My first visit was on the Air New Zealand inaugural flight in my first year in tourism. I found Industry leaders there whose companies were largely responsible for outbound Japanese travel were amenable to high-level visits and personal relationships, whereas I could not personally influence the volumes of arrivals from most other countries by visiting them and getting to know company and government heads. The Japanese leaders in 1980 also needed reassurance as well as relationships they could trust: I was pulled aside and advised in a very soft voice they could not send their clients to New Zealand, or any other country, if they were subjected to hostility, meaning abuse by people still angry over the Second World War. I was firm that it was highly unlikely, that the possibility that an individual, perhaps an ex-prisoner of war, might shout something could not entirely be ruled out but the overall New Zealand reception would be warm and supportive. They appreciated that the assurance was not bland.

The Ambassador Graham Ansell and his successors contributed our success. He hosted a superb dinner for the top eight or 10 Japanese tourist leaders, enabling me to talk to them separately and collectively, and accompanied me on some of my calls. But the hard working junior staff in our office, a small, tightly-knit group of New Zealanders and Japanese, were major contributors too.

I thought I was pretty impervious to new countries but Japan gave me something as close to culture shock as I have ever felt. Everything seemed homogenously Japanese, food, attitudes, even the leaves on the trees. One night on a later visit David Lynch organised a dinner with the eminent American writer on Japanese matters, George Fields. He advanced the view that Japanese (and Korean, Chinese and Singaporean) economic success was related to Confucianism, since this was not a doctrinaire religion but a set of notions that permitted flexibility. Rigid religious beliefs elsewhere held other societies back. Confucianism also encouraged a work ethic and gave the country a set of shared values which encouraged trust.

George also noted that there had been four great transitions in modern history – the American, French and Russian revolutions, which in each case meant more or less wiping the slate clean and starting afresh, and then the Meiji Restoration in Japan which retained much of the previous era’s values such as a commitment to craft. The Japanese pride in their work as defining their role in society had persisted throughout modernisation. He strongly affirmed that Japan would not adopt forms of modernisation which would weaken their basic values.

The social traits were also intensive – I felt that however much I studied how to hand over a business card or where to stand in a lift I would be unlikely to get it right. But when they tried English they got it wrong sometimes too. On a visit to Kyoto I returned to my hotel room one night to find the red light on my telephone glowing. A notice beside it said, “If red light glows there is massage for you at front desk.”

Developing a relationship with Japanese leaders was truly beneficial. They came to New Zealand, once with the whole board of JATA, their travel and tourism industry association. A culmination was the visit in 1988 of Japan’s Minister of Transport and Tourism, the notable Shintaro Ishihara, author of the highly controversial book The Japan That Can Say No, urging Japan to stand up to the United States. During his talks in Wellington he proposed there be regular Japan-New Zealand official tourism talks. We were that first country in the world that had such an offer and we of course accepted.

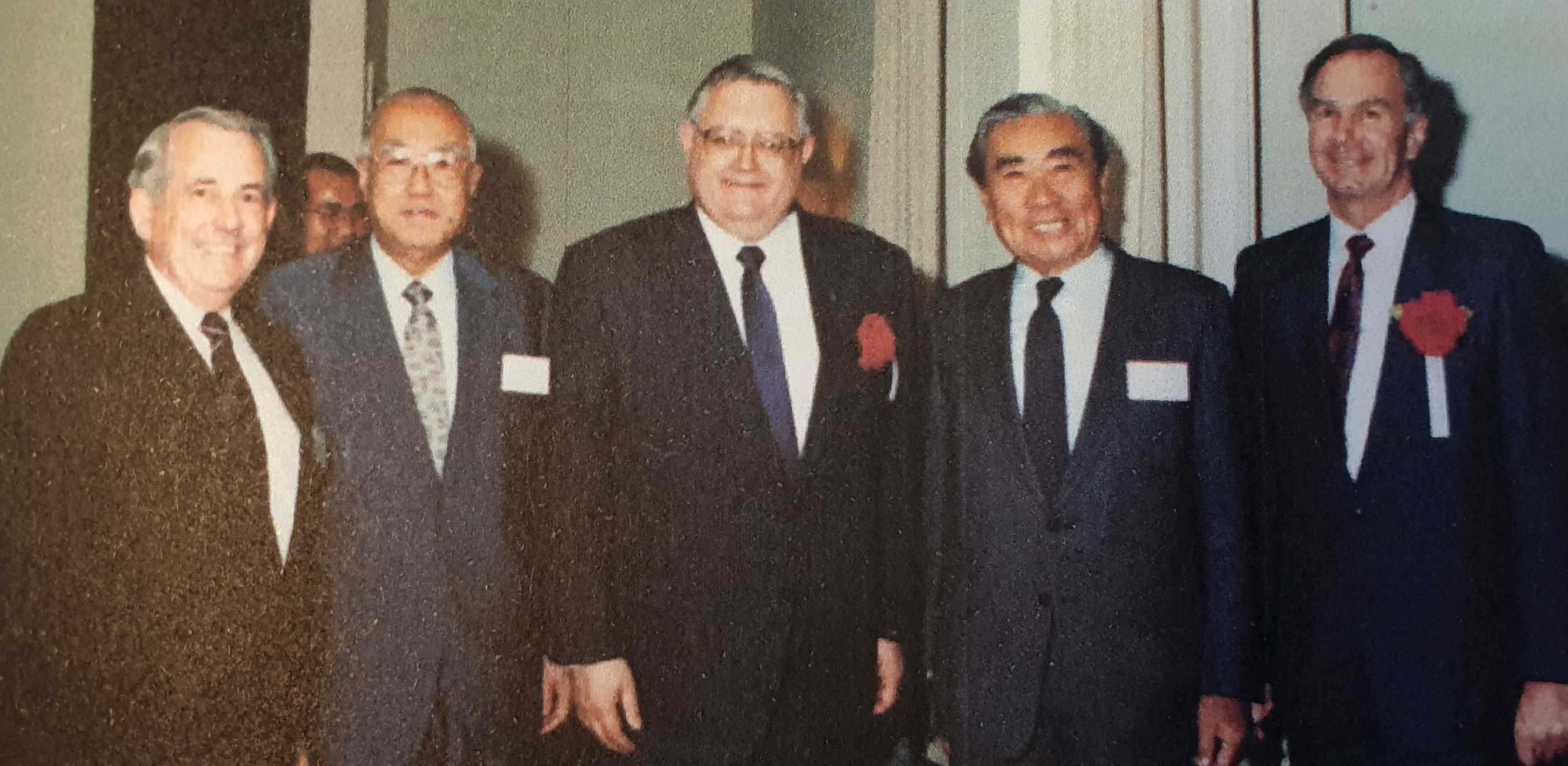

New Zealand ministers made periodic visits to Japan: here Japanese industry leaders meet with Richard Booard, travel commissioner in Toky, left Jonathan Hunt, Minister of Tourism, centre; Neil Plimmer, right. 1988.

He hosted a dinner in Christchurch on the evening before he flew out. Unfortunately no New Zealand Minister could attend so I fronted up with him and his delegation. It was not long into the evening before he decided to liven things up. The United States was racist in its trade policies he said, citing an attempt to take Japan to the World Trade Organisation over some trade practice. He developed this line at some length and with some vigour. I could see his officials, whom I knew, imploring me with their eyes and body language not to contest any of this. But such opportunities do not come often. I pointed out a few things, such as that the US was also taking the EEC to a WTO tribunal, so it was hard to see an anti-Japanese racist pattern, and we had a great evening.

The timing and location of opening other offices in Asia and elsewhere was an ongoing issue. I developed a rule of thumb that if a market was generating 15,000 arrivals a year and was serviced by direct flights then an office was to be seriously considered. On something like that basis we opened offices in Singapore with Derek Alabaster in 1983 and in Hong Kong with Connie So in 1986. The main variations to this practice were where our Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Department of Trade and Industry were opening offices (consulates) independently of us. These offered a low cost entry into a market, if we sent a representative to share in these offices. On that basis tourism staff were assigned to Perth and Adelaide (1982) and Osaka a couple of years later. This arrangement was useful – arrivals from Western Australia for example grew measurably - but not central and all three were closed in 1988.

The South Korean market was intriguing. Throughout the mid/late1980s it was apparent that the size and affluence of South Korea indicated that under normal circumstances it would provide a significant growth market for New Zealand. But because of Government controls there on access to foreign exchange, there was no “normal” circumstance. But in 1988/89 the major restrictions were lifted and South Korean non-business outbound travel commenced. NZTP moved quickly and in 1989 participated in the Korean Trade Fair, assigned a very able officer in Hong Kong to cover Korea and commenced a variety of other marketing activities. I know that we achieved 30%-40% growth in arrivals in that first year, of course off a very low base.

New Zealand’s first tourism mission to South Korea.

With Neil Plimmer (centre) and on his left Chris Butler, New Zealand ambassador; Rob Talbot (PATA Chair) and Ian Newman (Newman Brothers passenger coach firm)

With Neil Plimmer (centre) and on his left Chris Butler, New Zealand ambassador; Rob Talbot (PATA Chair) and Ian Newman (Newman Brothers passenger coach firm)

The following year Rob Talbot, former Minister of Tourism and at the time Chairman of the New Zealand Chapter of PATA, proposed that the Department and the Chapter lead a joint industry mission to Seoul. The benefit of this approach was that we could draw on the resources of the South Korean Chapter of PATA, an influential body that would help overcome our own lack of resources on the spot. And so I agreed. The mission was hugely successful, attracting many visitors to our presentation, strong media coverage and business for the firms represented. The arrival statistics from South Korea started to move up another notch within weeks of the visit. On the same trip I started a dialogue with the relevant Vice President of Korean Air on the possible commencement of flights from Seoul to Auckland, a discussion continued at subsequent opportunities such as PATA Board meetings which we both attended.

Overall by 1991 the decade-long market diversification objectives had resulted in the pleasing outcome that Australia, even with steady growth, had dropped to almost 35% of total arrivals, while Japan had grown to above 18%, third place behind the USA, and pushing the U.K. into fourth. Canada, other North Asia and Germany were all around the 4-6% mark.

We endlessly needed to expand the range of New Zealand’s product offerings and to tap into niche markets as these emerged. As one approach I pondered the notion of focusing on a different aspect of the country’s attractions each year. Britain had a heritage year, promoting castles and the like, then a garden year, and so on.

We concluded we would push New Zealand as a place for really good food, wine and other beverages. The quality of these was high and the notion linked fresh food with the clean, green natural image. I talked through this idea with the food industry and others around the mid-80s, and Charles Williams went to Britain to study theme years and the successful Taste of Scotland food and restaurant programme. We designated 1988 a food theme year launched under the umbrella of Taste New Zealand. We set up an advisory body to help manage this programme, which long outlived the year. I really enjoyed it. It brought together top “foodies” from restaurants, food writers (Annabel Langbein was special, because apart from her personality she usually brought fresh home cooking to meetings), teachers of chefs (Ted Bryant of the Auckland Technical Institute was a tower of strength), wine producers (Terry Dunleavy), hoteliers and the like.

It led to advertising being run in international magazines like Gourmet, which focused on food as well as travel, and to our media programme bringing out food writers to tour New Zealand. I flew to Christchurch to meet a group of American food writers from various magazines on their last night, to debrief them on what they felt about their experience. They were genuinely impressed. A comment that has stuck was by one eminent American that his biggest (pleasant) surprise was the discovery of kumara. He reckoned that if properly marketed New Zealand could make a killing through exporting kumara to New York.

The project was not only a marketing tool for widening New Zealand’s appeal. It had the ambitious goal of raising the standards of New Zealand restaurants. This was achieved through the Taste New Zealand Awards, which gave restaurants reaching required standards a plaque and the right to promote themselves as Taste New Zealand Restaurants, together with extensive publicity in NZTP’s and the Trade Development Board’s publications. A Taste New Zealand Directory identified all the qualifying restaurants together with information about food events, wine trails and the like.

The programme was thoroughly successful, attracting hundreds of applicant restaurants each year, and winning support from many organizations not always involved in tourism. The annual award ceremonies were regionalized, partly to emphasise that regional cuisines had a role in regional differentiation and promotion. Mayors and everyone become involved. One or two overseas restaurants specializing in New Zealand foods were given honorary membership. It grew and lasted until the Tourism Board around 1992/3 passed it to (I think) the Restaurant Association, which allowed it to whither. But it had made its contribution.

Other sectors demanded a similar engagement. Alistair Campbell facilitated the Farm and Home Hosting Association, for example, until it too could stand on its own feet. An Outdoor Activities Group was formed under David Brooker, in 1984. Later in the decade NZTP staff serviced a new Walk New Zealand group and the Sportfish Marketing Group.

By the mid-80s another newbie, incentive travel, emerged as a market of promise. At its heart were large overseas firms seeking high class but different resorts and destinations to send groups of employees to as rewards for high performance – and as an incentive to future performance. Unlike a conference bid, the focus was on special activities and high levels of personal service, to “spoil” the group. Some New Zealand locations, such as the volcanic region from Ruapehu to Rotorua in the North Island and Queenstown in the South, were readily able to gear up to the needs of this market. Incentive travel bidding was added to the tools of our overseas offices, and in the United States in particular. Brochures and videos were developed especially for this market, presentations made at incentive conferences and with industry partners an advertising campaign was launched in American incentive magazines.

Major events potentially brought big business and. More than most marketing activities, events required local involvement and a strong domestic capability involving people perhaps not normally in the industry. So a push for overseas events to be held in New Zealand needed a strong supporting structure at home. We formed an Events Unit headed by Mary Alice Arthur, who joined NZTP with extensive American and New Zealand marketing experience. It had a wide brief – promoting New Zealand as a location for overseas filmmaking, for example, was a part of it. The expression ‘hallmark event’ entered our language, for the big ones like the French Grand Traverse which came to the South Island in 1989. The effort was redoubled in 1989/90 to use New Zealand’s 1990 150th (Sesqui) celebrations as a reason for holding events in New Zealand or for visiting New Zealand because of the number of exceptional events available.

Home-grown events were also becoming important, especially for domestic tourism but also for regional differentiation. My speeches to regional meetings urged the merits of repeat or regularly scheduled events, since these have a steady drumbeat build-up as they get better, and better known. Every opera buff in the world knows of the Wagner festival every four years in a small town in Germany and makes up his/her mind to visit it some year. The wearable art festival then in Nelson provided a New Zealand example, and the same could be said of annual or bi-annual arts, wine, jazz, cherry blossom and other sorts of festivals. An annual directory of events New Zealand - What’s On was distributed world-wide.

Promoting New Zealand as a place to make films was plausible not only because of the country’s attractions but also our National Film Unit and other industry strengths. The efforts had their ups and downs. I had a call from Los Angeles saying that the film star Bo Derek, who had just completed the quite successful film 10 (which represented her scoring 10 out of 10 on an attractiveness scale) with Dudley Moore and Julie Roberts, wanted to make a film of Adam and Eve and to come to New Zealand to find a Garden of Eden location. That sounded pretty good so we facilitated that and she duly arrived, fully warranting her score. I took her and her agent around a bit on the first day, to see the NFU and a few places in Wellington, then delegated the task including escorting her around native forest areas looking for her Eden. That confirmed to the staff that their general manager was an odd-ball.

She found what she wanted not far from Nelson – a small lake surrounded by bush – and returned to Wellington to announce that she needed to import a snake. Why hadn’t we thought of that? She wanted a large boa constrictor, and argued, validly enough, that in our colder climate it would be very sluggish and unlikely to escape and harm anyone, and if it did it would be of a size easy to find and anyway could not reproduce. We hastily looked through the statute books and found that only the Minister of Agriculture could authorise the entry of a snake. Rob Talbot was the Tourism Minister at the time and he and Bo, with me bringing up the rear, trooped off to Duncan McIntyre’s office. I cannot say if he was more bemused by Bo or the request, but he thought it might be possible and said he would get back to us soon.

She flew off and before we had a definitive answer about the snake received a fax from her saying that the funding had fallen through and she was instead going to Spain to make a bull-fighting film called Bolero! It is a footnote to our disappointment that long after I met an American who knew something about the Garden of Eden project and asked me if I had seen the script and knew what was to happen between Bo and the snake. When I said no he responded drily, “If you had you might be pleased it was not made in New Zealand.”

NZTP was intensively involved with the industry in the coordination of marketing. We formed and managed a growing network of marketing groups – initially for Australia, Japan and Western Europe, by 1984 the U.S.A., and later others – with the airlines, inbound tour operators and major product operators such as hotel chains. Normally outbound tour companies in the origin markets selling New Zealand products were also involved. The groups shared research and other market intelligence, planned campaigns, organized specific promotions and events, agreed on cost sharing arrangements and many other activities, all with the intent of ensuring that NZTP’s destination marketing and the companies’ product marketing were as mutually reinforcing as possible. Most of these groups had a New Zealand base involving head offices, supplemented by local coordination between representatives in the markets.

A question which always hung around was whether to pool our marketing resources with others outside the industry. Should we market with other countries, especially Australia, and perhaps South Pacific island destinations? Should we market jointly with other export sectors from New Zealand? We tried them when there seemed a potential fit but the results were never great.

There were plenty in the industry arguing throughout the 1980s that the Australian market had such pulling power – the Thorn Birds and Crocodile Dundee were at their peak - that New Zealand should join with it and share in its future. Personally I was less convinced, at least about government-to-government level marketing. The yield from our tourism inflows was always a consequence of length of stay and daily expenditures as well as the number of arrivals and there was a significant risk that joint marketing would lead New Zealand to be a shorter-term add-on to an Australian holiday. Length of stay was already tending to reduce because of the shift from big annual holidays to shorter more frequent breaks.

More to the point was the underlying issue of whether New Zealand could stand on its own feet as a destination. We had reasonable evidence that it could. For example when the Japan market opened up, it regarded New Zealand and Australia as joint destinations and its wholesalers packaged tours that included both countries, typically 10 days in Australia and four in New Zealand. Hence in 1980, when Air New Zealand commenced direct flights Narita (Tokyo) to Auckland, NZTD adopted the goal of making New Zealand a “mono destination” – one to be promoted by Japanese companies as worthy of a tour in its own right. This approach succeeded, as shown over the following two to three years by our performance measure of steadily increasing the number of major Japanese firms offering solely New Zealand tours.

This in fact became a pattern for a number of new Asian markets: initially they wished to take in both countries on a tour; then as the market matured it quickly distinguished between them and developed separate tours.

But industry support for joint destination marketing remained intense. A growing number of New Zealand companies were investing in Australia, especially in camper vans fleets, and benefiting from the tourists in both countries. For these firms the potential loss of length of stay in New Zealand cut no ice, they could grab the other days in Australia. But some simply lacked confidence that New Zealand could make it on its own. Another and rather thick strand was Air New Zealand, which was firmly attached to the proposition that it wished to be both an Australian and New Zealand carrier, for both inbound and outbound, and of course for traffic between the two countries.

As Minister, Warren Cooper firmly bought into joint marketing. He and I visited Australia where he strongly advanced to the Australian Minister the proposition that overwhelmingly most of the global tourism flows went east-west or vice versa across the northern hemisphere. The task of drawing a proportion of those flows down under was beyond either Australia or New Zealand, but together we might have a chance. The Australians were polite but did not commit.

Then Queensland separately told us it was keen on Queensland/New Zealand marketing. It was developing its northern, tropical capability and saw a joint package with New Zealand, as a destination offering a complementary temperate climate, as being an attractive proposition. Warren Cooper and I met with the Queensland Tourism Commission’s Chairman Frank Moore, but it did not fly. Our Travel Commissioner in Tokyo, David Lynch, warned against it for reasons that Cairns, being only five hours flight from Japan and therefore able to compete with Guam or Hawaii, was attracting a mass beach-related market that we were not targeting and joint promotion with it could confuse the Japanese market and undermine the long effort we had made to build up our own image and reputation as an independent quality destination. The Australian Tourist Commission (ATC) also opposed the idea, arguing it would fragment its efforts to co-ordinate Australian federal/state marketing and implying that if the idea proceeded this would end chances of wider Australian/New Zealand joint marketing.

Almost every year I seriously engaged in discussion with the ATC on joint marketing, and periodically Ministerial talks were held. Fundamentally the ATC were not interested. Their CEO for much of the 80s, John Rowe, had a string of reasons: his Parliament appropriated his money for him to promote Australia and not to dilute this; he had a big enough difficulty coordinating the Australian states with the ATC’s efforts and to bring New Zealand into the picture would only complicate that; if the two countries came to be seen as one destination then flaws or bottlenecks in New Zealand product would come to haunt Australia and he couldn’t fix it (a shortage of rooms in Queenstown during the boom around1986/87 became a much-cited example of this point); and if Australia and New Zealand both marketed their own countries to maximum effect each would benefit and the outcome would be much the same as a good joint promotion might yield.

So he and I had parallel reasons for not pursuing this, but he did not have his industry on his back about it as I certainly had mine. We reached agreement on a few joint activities of mutual benefit such co-locating our booths if we were both at a big trade fair like ITB Berlin. The relationship was always congenial but rarely had much substance to it.

The Department’s, or perhaps more accurately my own, relationship with Air New Zealand was rather more fraught. Logically the relationship between a country’s tourist office and its national carrier would be close and supportive in every way, and it would have been great if that had been the case here. At a grass roots level it was, and in most markets most of the time there was good cooperation between NZTP and Air New Zealand representatives and much shared marketing activity. The higher level difficulties had a number of causes.

One was Air New Zealand’s strong commitment to promoting Australia. This sort of approach was not normal: British Airways was not dedicated to promoting France; JAL was not dedicated to promoting South Korea, and so on – but Air New Zealand was very committed to being an Australian as well as a New Zealand carrier. In my first year I was faced with a major decision on this. NZTP was planning a very major promotion in the United States which involved an expensive live and film presentation and a large group of company representatives to various venues in mainly in California, where audiences of many hundreds and sometimes thousands were invited after consultation with travel agents over their client lists. Air New Zealand participation was essential, but it asserted it would do so only if Australia was given equal time. In my bones I did not want this, but decided that long term cooperation with Air New Zealand was essential and acquiesced.

I actually went on part of that promotion, to see what such things were all about and to meet the industry, and sat through a superb film of Australia, as well as a superb film of New Zealand, at each venue. Old hand American travel agents asked me afterwards just what did New Zealand think it was doing? Would the ATC and Qantas do the same for us? Well, our capacity to resist this sort of Air New Zealand pressure grew rapidly after this and over time we were able to develop more sole New Zealand joint marketing with the airline – and with other carriers.

The airline’s commitment to dual destination travel sometimes extended to another country, besides Australia. When Air New Zealand started flying from Japan in 1980, it was not confident that it could attract Japanese tourists solely to New Zealand. It flew via Nadi in Fiji and in Japan it seemingly spent as much or more on promoting Fiji as on New Zealand. I constantly urged the airline, and particularly its very able Tokyo representative Mike Sano, to shift the focus, and after about three years that happened. But the issue threw into sharp relief the issues of industry multiple destination marketing versus NZTP’s mono destination focus.

Air New Zealand was also committed to marketing all of its route structure, and I had no qualms about that except that sometimes it seemed to be carried too far. Once in London I called at short notice on the Air New Zealand manager to reinforce our commitment to joint marketing, and asked him to brief me on his current marketing of New Zealand. With a little embarrassment he said that he did not have any, that the company was focusing on advertising its London to Los Angeles (and I think also Hawaii and Fiji) route.

Like all airlines Air New Zealand had a strong focus on outbound travel – taking New Zealanders overseas. Again that was not an inherent problem for us except when it seemed to lead to neglect of inbound. This often seemed to be the case with trans-Tasman travel, where we felt it would be appropriate to see a better match between Air New Zealand’s strong promotion of Australia to New Zealanders and weak promotion of New Zealand to Australians. Air New Zealand’s desire to be an outbound carrier from Australia led it, in that country, to concentrate on marketing its long haul routes, such as Sydney-Los Angeles, rather than the routes to New Zealand.

I concluded that if Air New Zealand was not interested in joint promotions out of Australia to New Zealand, then we could do them with other airlines that were keen. The Sydney office, around 1982, ran a promotion with Continental Airlines, which had just received rights to fly the Tasman. Air New Zealand did not think that carrier should be flying Australia-New Zealand, much less that NZTP should be seen to be supporting it. This led to some tense words, but the promotion proceeded.

We had difficulties about air fares too which often seemed prejudicially high. At one stage airfares from Singapore to New Zealand were excessive, and Qantas entered the field offering a Singapore-Sydney-Auckland fare that was its Singapore to Sydney fare plus one dollar. Air New Zealand was furious when our travel commissioner in Singapore welcomed this. At another time Air New Zealand offered lower airfares Vancouver-Sydney than Vancouver-Auckland.

Additionally, and unlike many NTOs, the department was a policy agency as well as the country’s destination marketing arm. In this context the logic of tourism growth required us to support liberal aviation policies. Air New Zealand strongly opposed these, seeking to retain historic levels of protection. Its culture was such that it could not support the Department wholeheartedly on marketing while feeling opposed by NZTP on policy. Once under the Muldoon Government when Rob Talbot was my Minister we decided, after the Government rejected an application by Canadian Pacific to fly to New Zealand, to make representations to the Minister of Transport George Gair. He listened to our articulation of the benefits to the economy of having more tourists on more airlines flying in, and memorably responded, “Why should my airline suffer for your hotels?”

This issue was only resolved when the Labour Government through Richard Prebble, first as Minister of Transport and then as Minister of State Owned Enterprises, successively deregulated aviation policy and sold Air New Zealand. He was working to an outstanding External Aviation Policy statement drafted by a team under Brian Lynch, deputy secretary at the Transport Ministry.

There was always some but not too much pressure to market tourism alongside our dairy products, carpets, or whatever, as part of a “New Zealand Inc.” approach to world markets. The idea had more appeal to the heart than the head. We joined in on occasion when the cost was low and the potential benefits had some credibility, such as by providing tourist posters and other support for New Zealand exporter participation in food and beverage promotions off shore. I recall a major promotion in Germany we ran jointly with Air New Zealand and the NZ Kiwifruit Authority. At one stage we supported a common New Zealand export symbol, the Miha, adopted and endorsed by the Minister of Overseas Trade, Mike Moore, who was also the Minister of Tourism.

But it was never a serious starter for us: we had different market segments to target and always little enough money to reach them, and tourism had very distinctive distribution channels, very separate from those of our trade exports. In a sense the issue reflected the profoundly different way that tourism operated from other foreign exchange earners: its process of bringing its buyers (the tourists) to New Zealand, their purchase of our destination as product “sight unseen” before departure, and their use of public goods – beaches and national parks, for example - while here were all distinctive attributes of the sector.

Large countries held tourism trade fairs in their own countries, bringing in the buyers from their overseas markets to meet the sellers on their own ground. By the late 80s I felt that the standard New Zealand view that we were too small to hold our own trade fair should be challenged. The outcome of a review was to proceed, and the Department organized the first New Zealand Tourism Exchange in 1989. It became a regular feature, immensely popular with the New Zealand product suppliers and popular enough with the overseas buyers, many of whom needed a business reason to visit New Zealand. The Exchange became what is now the hugely successful TRENZ, operated by the Tourist Industry Association.

I have probably made a decade of marketing sound very measured as we expanded into new areas and techniques at various appropriate times, based on strong research and collaborative planning. But life was not always like that: periodically some external event dislocated everything. My time in tourism started with an appalling strike by Air New Zealand and Qantas staff which stranded passengers in New Zealand for weeks and of course prevented new tourists from arriving. It damaged New Zealand’s destination reputation for at least two years and made high growth in the early 1980s impossible.

The world share market crash of 1987 was another total dislocation – tourism around the world was slowed seriously and our arrivals again took two years to recover. I concluded as a rule of thumb that tourism growth projections should always allow for two negative unknowns like that each decade, to produce two to four difficult years out of ten, which significantly dented any projected growth rate based on “normal” years. In the 1990s the Gulf War in 1991 and the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 were cases of this, slowing performance over that decade.

The upshot was still good. We achieved double digit growth in most of our good or normal years, and over two years 1985-86 we were the fastest growing destination of all OECD countries. It all averaged out at just over seven percent per annum over ten years. Early in the decade the Tourism Council and NZTP agreed to target a doubling of arrivals over the ten years and hopefully reach I million. In 1981 we were at 460,000, in 1991 it was 975,000.

Another measure was that over the decade we came from nowhere to being New Zealand’s largest foreign exchange earner. We over took forestry, fishing, horticulture and other lesser sectors, then in 1987 wool and dairying, and finally in 1988 meat, at the time the largest export sector. Tourism stayed at number one for a decade until the Asian Financial Crisis led to a downturn followed by a steep rise in overseas diary prices enabling dairying to gain the top slot. By 2015-16 however tourism was back as the leading sector in foreign exchange income.

To be engaged in all this was a fascinating privilege.