PORTRAITURE IN 3D, OVENDEN LECTURE

Portraiture in Three Dimensions, address to the New Zealand Portrait Gallery

30 November 2021

Thank you for coming, it is a privilege to talk to an audience such as this – an audience which unlike my speech is in four dimensions, if we count those watching out there in the ether, on Zoom I believe.

Thankyou Alan (Bollard, Chairman) for the kind introduction; to Brian, Denise, Bri and others for their great competency in managing this on again-off again covid-affected event; and I recognise and thank the founder/namer of this lecture series Dr Keith Ovenden.

Portraiture in Three Dimensions

It may not be the most exciting way to start a lecture, by defining one’s terms, but I feel the need to be a bit more specific about my subject. In two-dimensional portraiture, paintings, drawings and photographs mainly, but perhaps other media such as stained glass or tapestry, the portraiture is not limited to the face and upper torso. Full length figures also qualify, and a classic example has been right here where a few years ago a full-length painting won the Adam Portraiture Award.

I apply that same framework to three-dimensional portraits, not limiting them to heads and busts but including the full body, which is to say, statues: here is one close-by, a statue and a portrait of Peter Fraser.

Sculpture of Peter Fraser by Anthony Stones.

[Photo credit: Midnighttonight at the English-language Wikipedia,

CC BY-SA 3.0,]

Another part of my definition is that the face must be of a real person, and that includes self-portraits. A statue or bust of an anonymous figure does not count. But as we will see, these boundaries are not sharp, there is scope for transitional stages.

And another prefix you may puzzle over: all the illustrations I am going to show of three-dimensional art are of course in two dimensions. One day, perhaps soon, a button on a remote may be pressed and a hologram or similar 3D picture will come up, but sadly not tonight.

Other forms of 3D portraiture

There are other 3D portrait forms besides busts and statues, and one is reliefs, or bas-reliefs if they are shallow.

Bas-relief portrait

There is debate over this in art literature, with one argument that they are more akin to 2D art because they are dependent on a background, and are not free-standing, and therefore analogous to a painting needing a wall.

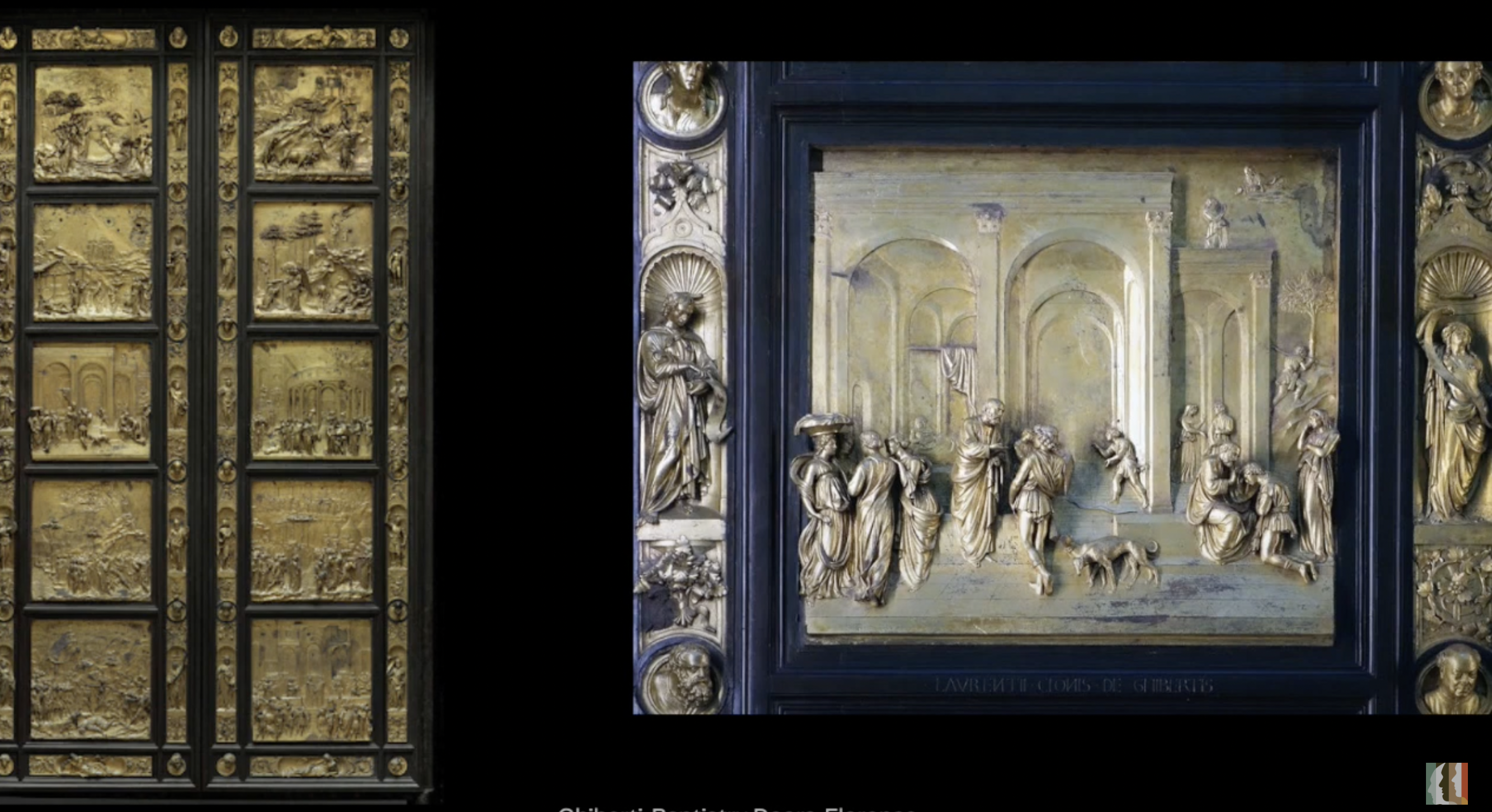

Ghiberti, Baptistry Doors, Florence

Another point in this direction is that that early Renaissance artists like Ghiberti, dealing in reliefs such as on his famous Baptistry Doors in Florence, seemed to feel that the three-dimensionality of a relief was not enough in itself and so experimented with perspective, applying the newly found single-point perspective technique, which we normally associate with 2D paintings. Indeed some art historians believe they developed this perspective technique first in the field of relief sculpture, and later applied it to paintings.

Whatever the debate, the depth of reliefs, and their techniques, often carving or bronze casting, lead me to include them, when of a person, quite firmly within the definition of 3D portraiture.

Kate Sheppard National Memorial, Margaret Whindhausen, Christchurch

Reliefs have a very long history and have been widely used overseas, but they are not common in New Zealand. The best known is probably the Kate Sheppard National Memorial in Christchurch, unveiled in 1993. It has six portraits of women significant in the fight for the vote. It strikes me as a quality artwork, if conservative in a sense, with clear representation of the features of the subjects, and a convincing way of commemorating a collective effort. It could well provide an inspiration for other memorials and artworks, to be executed in this form.

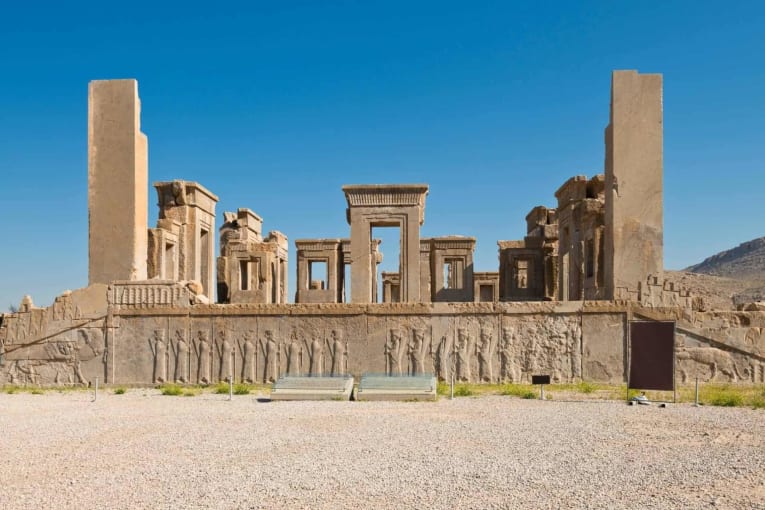

An early frieze; Persepolis, Persia (Iran), 5th Century B.C.

Where a relief becomes a continuous line of figures it becomes a frieze, but since I am unable to find a frieze portraying actual people, this form does not feature again here.

Left: Donald Trump mask

Right: Death mask, Dante

And yet another form is a mask. When of an actual person they are undeniably 3D portraits, but their use is very constrained, in New Zealand if not everywhere overseas, and they do not loom large tonight.

And delving deeper, there are death masks, made of wax or plaster over the face of the deceased. They were the product of particular societies and times, are rarely made these days because of the availability of photography to achieve the same purpose, and because they are simply moulded I don’t think they qualify as art.

Village of Dolls, Nagoro, Japan

And, courtesy of your Chairman, there is still another form, dolls. A fairly famous example is the town of dolls, Nagoro, in Japan, which is almost depleted of humans due to migration to the cities, and where an artist has been replacing people with life size dolls. Most are anonymous and do not qualify here, but a few are portraits, where the artist has made one of herself and another of her mother.

And tonight I have just found another, a mug in this hall with the face of Rob Muldoon.

3D portraiture in the context of trends in the visual arts

It is an intriguing part of the historical background to note that across the board in the visual arts for many decades, there has been a relatively weak role for the portrayal of the human body or specifically the head. At times there has been a tendency to avoid this altogether as a subject matter. Many of the great movements in 20th century art, from expressionism to minimalism to abstraction or modernism, made little or no reference to the human form. And when artists did, they usually, like Picasso, portrayed the figure or face as never before, or used the face in some wider social context rather than to focus on it as a portrait in its own right.

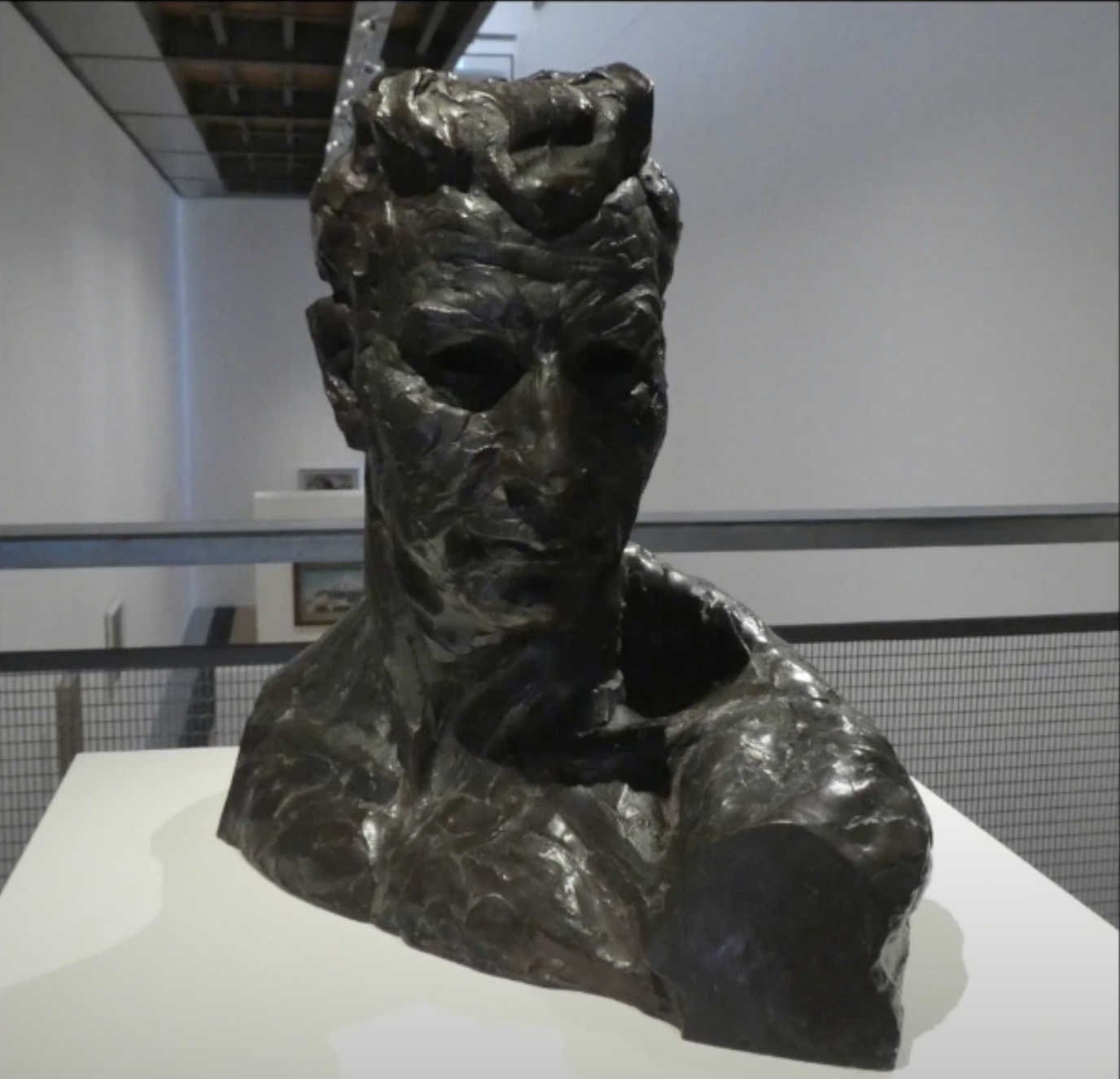

Right: Renato Giuseppe Bertelli, Head of a Mussolini, 1933

This absence can be illustrated in many ways. Robert Hughes’ magnum opus of Twentieth Century art, The Shock of the New, has 269 coloured illustrations, and only one is of a portrait in 3D – Bertelli’s Head of Mussolini, dated 1933.

Apart from its rarity, the photo of it shows how much can be lost in conveying a three-dimensional work in two-dimensional photography. If you look down on it, it is a series of concentric circles. And I have wondered if the artist was not subversively saying that his leader was two-faced.

Top left: Venus of Willendorf by an unknown prehistoric artist

Top centre: Nefertiti, Ancient Egypt

Top right: Marble head of a Goddess. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bottom centre: Head of Joseph, ca.1230. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bottom right: Edwardian-era plaster bust c.1910

One oddity about this relative neglect is that it is contrary to the whole prior history of the visual arts. If we jump across millennia, from the earliest art of homo sapiens – the so-called Venus figures, through to ancient Egypt, classical Greece and Rome, to the art of Europe from the Middle Ages to the turn of last century, the portrayal of the face and figure has always been a major focus of the visual arts.

Another oddity is that it is contrary to what science is telling us about what we humans like about art, which is artwork that veers to realism rather than abstraction. That realism of course very specifically includes portraits and the human figure.

For example, one study suggests most of us prefer art that is not straight literalism or photo-reality, but which tends to that. It shows that most people’s brains light up most strongly when shown an artwork which has about a 20 percent variation from reality. It seems some interpretation is expected and valued, but if you move more than 20 percent away from reality in the direction of abstraction or distorting the object, you will lose viewer interest.

Another piece of research, based on the manner in which the pupils of our eyes expand when we see something appealing, such as an attractive person, and contract when we see something we view negatively, such as a shark, claims that most people’s eyes contract when faced with abstract art. This too reinforces the notion that popular art resists abstraction, and in supporting art that is closer to realism, it supports art that is figurative, including portraiture.

It would be for these reasons that despite a contemporary art world preference for contextual and abstract-tending art, there has always been a steady, underlying popular support for figurative art and portraits.

Above: Another Place, Anthony Gormley

Below: Lying Naked Woman, Fernando Botero

In recent decades, despite the marked decline in commissioning statues and busts as memorials, the figurative works of artists such as Antony Gormley or Fernando Botero have been endlessly popular. They probably loosely fit the formulation of around a 20 percent variation from true life realism, but they still do not qualify as portraits.

Left: Helsinki Sibelius memorial, Eila Hiltunen

Right: The Face in the memorial

There are some rather interesting combinations of art works embracing both contemporary sculpture, and realistic portraiture in the form of a bust. My favourite is the Sibelius memorial in Helsinki by the Finnish sculptor Eila Hiltunen. The main component is a wonder, in that if any physical three-dimensional artwork could capture a sense of music, this does it. The stack of tubes might reference a collection of clarinets or other woodwind instruments, or organ pipes, but one way or another, collectively they say music.

Then alongside is a bust of Sibelius, so you see the face of the man himself. The total work in this dual format could be another model for other commemorations.

And so at this point, we can see trends in 3D and 2D art moving in a sort of rough tandem, both seeing a weaker focus on portraiture and the human form than in past periods of art history, but with this subject nevertheless showing an underlying persistence with popular appeal.

How do 3D and 2D portraits differ?

We can reflect on how 3D and 2D portraits differ. To a degree, this is a subset of a wider debate that has been engaged in for centuries over the relative merits of sculpture – read 3D – versus painting – read 2D. Michelangelo and Leonard da Vinci engaged in it, Michelangelo for sculpture, Leonardo for painting. I have to say that there is more than enough for tonight to keep the debate focused on portraiture.

The free-standing nature of a portrait sculpture is the obvious starting point. The artwork is not just a visual image but a physical object, and one usually of firm and durable material. It stakes out a dominant claim to ownership of its space.

From that positioning it invites the viewer to walk around it, to engage with it from different perspectives. These are unique characteristics.

Left: The Empress Vibia Sabina (c.130 A.D.), Museo del Prado Right: Bust of Christopher Perkins, Francis Shurrock

This three-dimensionality greatly widens the scope for depth in the image through light and shade. The shadows are real, not painted on. The possibilities for depth and shade are hugely widened by the different textures available – a bronze portrait, contrasting with the marble, illustrates this.

The variety of materials offers another point of difference. There is a fair range available to the 2D portraitist: various paint forms, pencil, crayon, charcoal, and I suppose anything that makes a line. And there is a variety of backdrop material too: canvas, hardboard, paper and the like. Many painters and photographers pay great attention to the choice of their base material.

But for all these options it must be said that the variety available for 3D portraiture is much, much wider. Fundamentally different materials range from bronze and other metals, wood, glass, stone including marble, plaster, fibre glass, plastic and so on. Some of these options have resulted in stunningly creative and attractive outcomes such as this glass sculpture of Kate Sheppard in the National Library.

Kate Sheppard glass sculpture, Propellor Studios, at the National Library

Another difference is that 3D portraits, certainly in the form of statues but less so for busts, are normally found outside in public spaces, like the Peter Fraser we showed, while 2D portraiture, with an exception for murals, enjoys a strongly indoors environment. This has a number of implications relating to the issue of how public art in parks and on streets differs from art in other places such as homes, galleries, or offices, which is a separate subject in its own right.

The main consequence is that outdoors public art, including statues, is pulled in a more populist direction, and tends to be less abstract, because the audience is more diverse and usually composed of people who are not intentionally viewing art.

Left: Unknown man on bench

Right: Public sculpture

Manifestations of this populist public art are often figures of no-one in particular in some posture that the audience can easily relate to and even interact with. A bronze of a person on a seat permitting viewers to sit beside him and be photographed, or of a tourist taking a photograph, are common examples found in many cities around the world. By my definition, these anonymous figures are not portraits, and they do not feature again here.

It can be argued, further, that another difference is that 2D portraiture is more widely available, or accessible, in terms of the subject person, whereas the bust or statue of a particular individual is far more likely to be limited to famous people and therefore to be more imposing. A portrait exhibition here, earlier this year (2021), emphasised that the portraits in paint were an act of power “utilised as tools of state and institutional power…” True of some, but this argument is writ much larger in its application to busts and statues. These particularly represent the established and the powerful – here (Menshikov, below) is a somewhat overstated example to make the point.

Left: Menshikov

Right: Example of a standardised portrait sketch

Historically if a society has wanted to convey the high status of a person there has been no more effective means of achieving this than through a marble or bronze bust or statue. Whereas many non-famous people have their portrait sketched or painted, and you can see this happening at fairs and tourist places everywhere: few who are not eminent public figures would have a bust made.

Still another point is that normally one can touch a 3D portrait, perhaps not every classical Greek bust in a museum, but most statues, reliefs, and other forms. So they offer a tactile experience, not available with a painting, which is normally, severely, hands off.

Paul Revere

But for all these strong and differing characteristics of the three-dimensional portrait, it is appropriate to recognise that there are some qualifications to how dominant its separateness is from 2D portraiture. The skill that artists have developed for simulating light, shade and depth with paint and colour variation on a flat surface is remarkable. The techniques range from subtle changes in colour and soft edges, as in Italian sfumato, to the sharpest of contrasts, as in Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro. And sometimes just with thick paint, impasto. You have all heard of trompe l’oeil, the technique of deceiving the eye into seeing 3D on a flat surface.

The Music Lesson, Johannes Vermeer. c.1662–1665, and detail

The Music Lesson, Johannes Vermeer. c.1662–1665, and detailThe painter artist sometimes uses other contrivances too, to try to match three dimensionality: a mirror, showing the portrait from a different angle, or the reflection of a face in still water, are further means of giving a rounded rather than a single perspective view of the face. Yet another approach has been to paint the same head from different angles, as van Dyck did here with his three angles portrait of Charles I, a painting which he did, interestingly, to commission a bust of the king.

Left: A Little Girl Looking at Her Reflection in a Pond, Jessie Wilcox Smith Art Prints

Right: Triple Portrait of Charles I, van Dyke. 1635 or 1636. Royal Collection

Hughes in his book notes that Picasso and Braque wanted to represent the fact that our knowledge of an object is made up of all possible views of it: top, sides, front, back, and tried to capture this in some of their art works. Hence one way or another, a flat surface artist can narrow the gap with their three-dimensional counterpart.

I will go so far as to say that in one detailed area, the painter can often do better, and that is with eyes. Eyes are openings into the personality of the subject, and are mastered by some artists but not easily by sculptors making portraits out of solid materials.

Not all observers will soften the 2D-3D differences in this way. The eminent British historian Norman Davies writes, “the impossible task of the historian has been likened to that of a photographer, whose static two-dimensional picture can never deliver accurate representation of the three-dimensional world.”

But without making a qualitative judgement that one is better than the other, the multiplicity of differences leads to another clear conclusion, that 3D portraiture is not just a variant or extension of 2D portraiture, but a quite significant art form of its own.

Defining Portraits as Individuals

I mentioned the definition that a portrait must be of a real person, but that the lines can be blurred. This ambiguity goes back a way, and I will go as far as medieval carvings of busts of saints. These purport to be of a particular person, when they have been recently sanctified, but since it is improbable that the sculptor ever saw the saint or an accurate portrayal of the person, it is likely that the face is the sculptor’s imagination. Here is St Margaret, a very real looking portrait.

Reliquary Bust of St. Margaret of Antioch, Niclaus Gerhaert von Leyden. 1462-1473.

Art Institute of Chicago

So it is a ponderable, that if the artist’s clear intention is to portray a real person, but it is uncertain if they have achieved a likeness, whether the boundaries of portraiture could be widened to include it.

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, Edgar Degas. 1800–1801. Cast c.1922.

Another blurring is when the face is clearly of a real person, but they are not identified. Here is one by Degas, of a 14-year-old dancer, but she remains unnamed, the official title of the sculpture being simply Little Dancer.

Per Capita, Cathryn Monro. Cable Street, Wellington

Per Capita, Cathryn Monro. Cable Street, WellingtonThere is an example here in Wellington, in the sculpture Per Capita by Cathryn Monro outside the QT and former Museum Hotel. The girl in profile is not named, but this is a portrait of the artist’s daughter.

And this sculpture offers another blurring, between two and three dimensional. It is a sculpture, not a painting or drawing, but its flatness denies it those characteristics of depth and shade normally associated with 3D portraits. It is a two-dimensional cut-out with the materials and the scale to qualify as a sculpture.

The blurring over portraits can be extended further by including busts or statues of anonymous persons as portraits in special circumstances. There is a new turn in the last year or so, with certain figures deemed to have taken an identity that is representative of a contemporary group or issue, prominently of black people reflecting the Black Lives Matter movement.

Reaching Out, Thomas Price. Stratford, UK

This is one in England named Reaching Out, but popularly called Black Everyone, nine feet high, and described by the artist as a “fictional construct” modelled on several women but specifically not just one.

Rumours of War, Kehinde Wiley. New York

And here is one in New York called Rumours of War. It is clearly modelled on the statues of Confederate generals, but the general on the horse is replaced by a black person in contemporary clothes.

These sculptures, and some current paintings in Tate Britain, are deemed to be more than just anonymous persons but timeless and universal representations of a black person in today’s world, and of the problems they face. Portraits of a state of being, some are saying.

It is likely that other such statues will follow, not limited to black people, but typifying other groups involved in high profile social issues. A person representing transgender persons or an indigenous minority might be examples.

I think we may well regard such artworks as portraits, portraits of a significant section of our societies in a particular situation. Their context is quite different from the bronze of an anonymous man sitting on a bench. Perhaps we can coin a new term for these, ‘collective portraits.’

Self, Marc Quinn

More ambiguities and experimental forms will arise, with artists’ creativity or new technologies. The British sculptor Marc Quinn has a 3D self-portrait made of his own blood, which needs to be constantly refrigerated.

Another recent innovation is an advertisement in The London Review of Books seeking participants in a project whereby the artist will make a portrait based on a phone call in which he hears the sound and energy of the participant’s voice! It may not be too late to offer to participate, and become part of art world history.

Contemporary Trends: Politicising 3D portraiture

The trend to collective portraits is tied to another, the current politicising of 3D portraiture. Statues of real people, historically, have frequently been political in the sense of reinforcing the established authority. The dimensions, the solidity, and the prominence of the location in a public space all serve to underline this projection of power and importance through statues. Which is fine if the person deserves it.

Very recently, statues have become political in some non-traditional senses. One manifestation is to question and remove statues, in the context of current political concerns. An American academic has coined the expression “landscape unfairness” to convey the underpinning of this trend, stating that the statue and its surroundings can “make selective accounts of the past seem normal.”

In the past year or so, concerns over this have led to violent actions against the statues of some people. As you are aware, many important people have mixed backgrounds. Prominent community leaders and philanthropists in Britain some time back were also slave traders, and in the United States some eminent confederate generals were also slave owners, and the destruction or removal of their statues has followed.

In Belgium there has been opposition to statues of people involved with Belgium’s colonial past, deeming these to be racist. In New Zealand the statue of the British army captain Hamilton has been removed.

Captain Hamilton, Margaret Windhausen, being removed from Civic Square, Hamilton City.

Captain Hamilton, Margaret Windhausen, being removed from Civic Square, Hamilton City.Photo by Chrisel Yardley/STUFF

In Mexico, this has been carried further – a statue of Christopher Columbus, an explorer deemed to be the forerunner of unacceptable colonialism, has been removed. In that same vein we have had a few calls here for statues of James Cook to be removed.

It is an interesting aside to note that a recent opinion poll, a large but unspecified number of New Zealanders supported the removal of colonial statues, but when this outcome was broken down by ethnicity, a significant majority of Maori were in favour of keeping them.

The Mexico City situation is particularly interesting because it is still an ongoing saga. It was announced in August that the Columbus statue was to be replaced on the same site by a sculpture of an indigenous woman, representing 500 years of suppression.

But then there was an activist outrage that the sculptor, a white male, had no authority to depict an indigenous woman, and the council in September conceded this, withdrawing the contract – but still planning to have an indigenous woman sculpture.

Pre-Hispanic sculpture, 6-feet long, to be replicated three-fold heightin a new sculpture, Mexico City

More recently still, it has been announced that the replacement is to be a replica of a pre-Hispanic sculpture of an indigenous woman, unearthed early in 2021. The sculpture is to be three-fold in scale to the original.

All this in turn has been vigorously met by a well-supported petition demanding that the Columbus statue be reinstated. And it may be, on a different site in city.

Similarly there is demand in New York for a statue of Columbus to be taken down on the grounds that he represents white supremacy.

This political approach of destroying statues has applied to living as well as historic figures, shown by the downfall of a statue of the current queen, Elizabeth II, in Canada.

The issue of whether such statues of slave traders, confederate generals, colonialists or their preceding explorers should be retained, as a reflection of history as it was, or even as meritorious art works of the time, as opposed to their destruction because of the foibles, real or alleged, of the person represented, is one I might avoid by saying it is beyond the scope of this lecture. But I do think a decision and outcome should be the result of a social consensus.

One compromise has been to remove statues that have given offence from their place of public prominence and to relocate them in a warehouse or museum. That holds open a fully considered decision about their placement sometime in the future.

Another very recent solution is the City of London’s decision to reverse a decision it made early this year to take down two statues of eminent persons who were also slave traders, saying the statues will remain but with new, explanatory texts alongside.

Edward Wakefield and the first Duke of Wellington, Francis Shurrock.

Wellington Centennial Memorial

Sculptures of people in Wellington have not been the subject of any such attacks recently or demands for removal. The nearest that I am aware of is one demand that the busts by Francis Shurrock of Edward Wakefield and the first Duke of Wellington, embedded in the Wellington Centennial Memorial on Mt Victoria, should be removed or at least deprived of heritage status, on the grounds that they represent a racist, colonial past. They are apparently quite frequently vandalised, but so far, they have stayed put.

Another manifestation of this politicisation is a very recent revival of installing statues of specific people for social or political purposes. Two such statues have recently been launched in London – one of Princess Diana and one of a Mary Wollstonecraft. Both have been commissioned for a purpose other than art or simply portrayal, and neither by the London Council. Diana’s has been projected as a strong statement by her two sons about the significance and role of their mother, and her side of the family.

Sculpture of Princess Diana, Ian Rank-Broadley, 2020.

The other is more overtly political. Wollstonecraft wrote a book on the rights of women in 1792, and it was a late and recent recognition of the importance of this which led to her statue.

A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft, Maggie Hambling

It is noteworthy that both statues have been controversial for their artistic merit too, or lack of it, quite apart from any wider issues they represent. Certainly the idea of commemorating an 18th century female writer as a nude is puzzling – although we have our equally puzzling statue of Labour Leader Harry Holland in the nude.

Left: A bust of George Floyd, New York RIght: A sculpture of Jen Reid (Surge of Power). Temporarily in Bristol, UK

Other examples of current political portrait sculptures again relate to the Black Lives Matter movement. There is the bust of George Floyd installed in New York, and the statue of the woman black leader Jen Reid temporarily in Bristol in England.

I will forecast that this trend for political and social voices and commentary to be expressed through sculptural portraiture will continue, through demands for removal, and for the installation of sculpture of both specific portraits such as those I have just mentioned and through what I earlier called “collective portraits.”

3D Portraiture in Wellington - statues

Let us look closer to home and see what there is around us. There are the statues of an earlier period, commemorating our most famous leaders. They start with Queen Victoria, move through the politicians in Parliament grounds and elsewhere, and end with Sir Keith Holyoake in Molesworth St. Each of these has a realistic portrayal of the subject’s face. Consistent with the trend I have noted, there is no statue of a New Zealand political leader or head of state since Holyoake’s, installed 30 years ago.

Pictured left to right:

Queen Victoria statue on Kent Terrace, Alfred Drury, 1911;

Keith Holyoake statue by Roderick Burgess;

Mahatma Gandhi, Government of India;

John Plimmer, Tom Tischler

There are not many other statues around Wellington of particular people who are not our politicians. There is Gandhi, donated by the Indian Government, and John Plimmer, commissioned by the City Council to commemorate Wellington’s sesquicentennial, and they too are characterised by realistic portraits of their subject.

Left: Solace of the Wind, Max Patte, 2008

Right: Quasi, self-portrait of the artist by Ronnie van Hout. City Gallery Wellington

T urning to more contemporary and less literal sculptures of the human form, the most obvious are Solace in the Wind, Per Capita, the cut-out sculpture I discussed earlier, Quasi, qualifying as a self-portrait of the artist and Woman of Words, the Katherine Mansfield piece by Midland Park.

Katherine Mansfield Woman of Words, Virgina King

The Mansfield has an interesting context. Of 30 significant sculptures commissioned by the Wellington Sculpture Trust over nearly 40 years, this is one of only two, with Per Capita, that can be called figurative, and a portrait.

Reflecting those trends of recent times I have noted, it will not be a surprise that the selection process for this work was the most fraught of any I have been involved with. But the public feedback since its installation suggests it is one of the most popular artworks the Sculpture Trust has installed, even if it is still not universally acclaimed.

This is may well reflect that popular liking for sculpture that incorporates the human figure, even though this one is not fixed on realism, like the Holyoake or others. It is not easy to measure and apply that 20 percent variation to a sculpture, but plausibly the Mansfield sculpture in Wellington, being over life-size and somewhat stylised, just fits this prescription.

Solace on the Waterfront may be popular for much the same reasons, but since it is of an anonymous human it does not to qualify as a portrait.

3D portraits in Wellington – heads/busts and reliefs.

Head and shoulder portraits or busts are less of a feature than statues in Wellington’s art scene, and those there are, tend to be indoors, which makes them less accessible.

Left: Old Identities head busts, artist unknown. Wellington Museum

Right: John Martin, one of the Old Identities

Nevertheless, Wellington made a good start in this field with the 30 Old Identities heads installed on the Albert Hotel, on the corner of Willis and Boulcott Streets where the St George is today, in 1877. Thankfully, most have survived and can be viewed at the Wellington City Museum. They are carved in wood by an artist unknown, but from all accounts they have an accurate likeness of their subjects. Here is one John Martin. Collectively they are the best representations of Wellington’s leaders of that time.

Tupai, Nelson Illingworth, 1908

Other busts and heads in Wellington are also tucked away inside, many of high quality. The largest number is at Te Papa, which has over two dozen in its collection. Of these, a group of particular interest are those made by the Sydney artist Nelson Illingworth on commission in 1908. They are mainly of particular Maori leaders of the time and certainly qualify as portraits in 3D. They are delicate, in plaster, never meeting the final intention of casting them in bronze.

Allen Curnow, Anthony Stones. Alexander Turnbull Library Collection

Another group really, really tucked away are eleven busts of famous New Zealand writers and historians by our eminent expatriate sculptor Anthony Stones, stored in boxes in the Alexander Turnbull library – here is one of Allen Curnow. They have just been photographed for placement on the library’s website, and may be on physical display soon.

Thankfully, not all of Stones’ are so confined. His bust of our prominent playwright Bruce Mason is up the steps inside the Hannah Playhouse and accessible at times when the building is open. And to revert to statues, the Peter Fraser I mentioned before is one of his, but appallingly the information plaques around it do not recognise Stones as the sculptor.

As for reliefs, the only examples with any profile I have found in Wellington are those around the base of the Queen Victoria statue, the most significant being that of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. They are by the same artist, Alfred Drury, who did the statue above. Here is another that just qualifies - a bas-relief of Edward Gibbon Wakefield on The Terrace.

Left: Queen Victoria Statue on Kent Terrace, Treaty of Waitangi relief, Alfred Drury, 1911

Right: Medallion, Edward Wakefield

Māori carving

A very distinctive and New Zealand category of 3D portrayals of the human face is of course Māori carving. My comments on this are simply designed to look at such art or artifacts in the context of this discussion, in relationship to the national and international trends and characteristics of three-dimensional portraiture, an outside view so to speak, and do not represent an authoritative Maori perspective on the art works and issues.

Left: Māori Head, 18th Century, unknown maker. European Collection

Centre: Post FIgure (Poutokomanawa). c.1840. Ngāti Kahungungu

Right: Māori relief, Gisbourne

But clearly Māori carving encompasses all the main 3D portrait variants, of heads or busts, full length body portrayals, and reliefs. In contrast with most New Zealand art, reliefs are the most widespread.

The traditional carvings reopen the debate over whether portrayals of non-specific persons can be portraits. Where they are authentic, as opposed to those carved for the tourist market or other purpose, they are described by authorities as representations of ancestors or progenitors of the tribe, or of an ancestral god, without purporting to represent a particular person.

I am inclined to suggest that the deep cultural significance of these portrayals, the reality of the ancestors in oral history, and the importance of linearity and continuity that is represented - a feature that Māori art shares with the art of many other societies around the world - warrants their inclusion in a discussion of portraiture.

They may be deemed, to use our newly coined terminology, collective portraits – but different in the sense that the Black Lives collective portraits are horizontal, across an ethnic group at a particular time, while these collective portraits are vertical, going back through time, through an extended family ancestry.

Left: Self-portrait of Raharuhi Rukopo. (1840s)

Right: A rare pair of Māori busts, carved out of Kauri gum. Ngāti Porou chief Tamaiwhakanehua and his granddaughter, Princess Te Rangi Pai. Private collection

Aside from that, there is also some tradition in Māori sculpture that is clearly portraiture of specific people. Here is one, a self-portrait dated in the 1840s. Here is another early one, a pair, carved from kauri gum.

There are more recent carved portrayals based on real people and clearly qualifying as portraits. There are two at the VUW marae in Kelburn, one a portrait of a particular Māori chief, the other of a Māori staff member, and there were two in the exhibition here a month or two ago, one in clay and one carved from andesite stone, but none of these could be photographed.

It is very likely that we will see more contemporary carved portraits of Māori, some distinctly of individuals and others that may be portraits in that collective sense. Both forms are likely to provide a compelling perspective of an ethnic group, Māori, and its social situation, and will frequently be conveying a political message, overtly or implicitly. They will be a major part of the next round of New Zealand’s portraiture.

Conclusions

To look ahead briefly, the scope for portraiture in 3D is likely to expand dramatically in the near future as new technologies become available. Holograms of human heads are already widespread, and this will lead to the more high-tech production of digitally interactive figures, and to movement. The production of portraits using 3D printing will surely be exploited too.

Hologram Portrait, Chuck Close

I had thought I would cover in this address the 3D portraits in the NZ Portrait Gallery – but there are none. There is an opening here that I hope that will be realised one day soon, and I have an insider’s track on one that will come as a bequest: this rather good self-portrait in bronze of the expatriate artist Douglas McDiarmid. May it be a foundation piece of a growing collection.

Bust of Douglas McDiurmid. Private collection

I express the hope that one day the Gallery may be able to hold an exhibition devoted to portraiture in three-dimensions. It might display the Illingworth heads from Te Papa, the Anthony Stones heads from the Turnbull Library, and the Old Identities from the city museum. It could include both literal portraits and some that I have called collective portraits. Hopefully it would include some very contemporary portraits, not necessarily made of blood or based on a phone call, but some hi-tech and moving portraits in the manner of holograms and other artificial intelligence-based and digital media, including the current overseas fad for a form of blockchain art called NFTs, all of which would be a big drawcard.

Marble portrait bust of the emperor Gaius, known as Caligula, Metropolitan Museum of Art

And I must say, as a non-artist, that I think portraiture is one of the most difficult forms of visual art. I could imagine sort-of making a go at painting a still life or some such subject, but an accurate portrait seems far out of reach. And while painting a portrait may be challenging, making a portrait in three dimensions must be even more so. With clay or plaster it would be hard enough, while to carve a portrait in marble looks impossibly difficult. My admiration for those who have succeeded is immense.

Thank you.

Neil Plimmer MNZM